Are corrosion failures, surface rust, or premature wear compromising your steel components? Are coating defects, weld issues, or fabrication delays disrupting your production?

According to ISO 1461, “zinc coatings provide sacrificial protection to steel, extending service life in corrosive environments where uncoated steel would rapidly degrade.”

Understanding galvanization—how it changes surface behavior, affects processing, and impacts service conditions—is critical for avoiding costly errors. In this article, we examine what galvanization really means for structural integrity, weldability, hardness, and long-term reliability.

Galvanization Overview

What Is Galvanization?

Galvanization is a surface treatment process that applies a zinc coating to steel or iron to improve corrosion resistance. The most common method is hot-dip galvanizing, where the base metal is submerged in molten zinc. Other techniques include electrogalvanizing and zinc spraying, each with specific industrial uses.

Why Zinc?

Zinc is anodic to steel, meaning it will corrode preferentially and protect the underlying substrate. This sacrificial behavior makes zinc coatings effective in harsh or moist environments. The oxide film formed during exposure also slows further corrosion.

Common Standards and References

Galvanizing processes are governed by standards such as ASTM A123 for structural steel and ASTM A153 for fasteners. These documents define minimum coating thickness, adhesion, and visual quality criteria, ensuring consistent corrosion protection in manufacturing.

Galvanization Process

Surface Preparation

The success of galvanization begins with surface preparation. Steel must be chemically and mechanically cleaned to ensure proper bonding between the base metal and zinc. The standard cleaning sequence includes degreasing to remove oils, pickling in diluted acid to eliminate mill scale and rust, and rinsing to remove residual contaminants.

After cleaning, the steel is treated with a flux solution, typically zinc ammonium chloride. This fluxing layer prevents oxidation before immersion and promotes metallurgical bonding during galvanizing. If any contaminant remains on the steel surface—oil, paint, welding slag, or oxide—the zinc layer may not adhere properly, leading to uncoated spots or peeling. For critical applications, surface cleanliness must meet ISO 8501-1 or similar standards before zinc application.

Hot-Dip Galvanizing

Hot-dip galvanizing is the most common and robust form of galvanization. The steel is fully submerged in molten zinc at approximately 450°C. A series of iron-zinc alloy layers form through diffusion reactions, with a final outer layer of pure zinc.

These alloy layers are integral to the steel substrate, making the coating highly resistant to mechanical damage. In contrast to paint or electroplating, this metallurgical bond cannot be peeled or flaked under normal service conditions. Coating thickness depends on immersion time, steel chemistry, and surface roughness but typically ranges from 45 to 85 microns, offering decades of corrosion protection in moderate environments.

Large or irregularly shaped components may require slower immersion and removal rates to ensure uniform coverage and avoid trapping air bubbles or uncoated zones. Galvanizing bath composition and temperature must also be tightly controlled to meet specifications like ASTM A123, ISO 1461, or EN 1090.

Electro-Galvanizing and Zinc Spraying

Electro-galvanizing applies a thinner zinc layer (5–15 microns) using an electrochemical process. It produces a smooth, bright finish and is widely used for automotive body panels and fasteners. However, its corrosion protection is more limited than hot-dip galvanizing, especially in marine or industrial environments.

Zinc spraying, also called metallizing, involves melting zinc wire and spraying it onto the surface using a combustion or arc gun. It is used for very large structures, repairs, or components that cannot be immersed. To improve durability, sprayed coatings are often sealed with epoxy or silicate-based sealers.

Each method has distinct advantages, and the selection depends on part geometry, service environment, expected lifespan, and downstream processing needs such as welding or painting.

Post-Treatment and Inspection

After galvanization, steel parts are cooled in air or water. They may undergo passivation treatments to reduce the formation of white rust during storage. Inspection is conducted according to standards such as ASTM A123, A153, or ISO 1461. Key quality checks include:

- Coating thickness (measured by magnetic gauges)

- Adhesion and continuity (visual inspection)

- Surface defects (lumps, runs, bare spots)

For critical components, additional tests such as cross-section microscopy or salt spray testing may be performed. Inspection documentation is often required for infrastructure, utility, and marine projects, where long-term durability is contractually enforced.

Surface and Coating Behavior After Galvanization

Effect on Steel Surface Characteristics

After galvanization, the steel surface undergoes significant physical and chemical transformation. The zinc coating alters surface texture, color, and topography, which directly affects downstream manufacturing processes such as painting, forming, and assembly.

In hot-dip galvanizing, the formation of zinc-iron alloy layers results in a matte-gray appearance with a characteristic spangle pattern. The roughness varies depending on the steel’s silicon content and cooling rate. Silicon-killed steels may produce thicker, rougher coatings due to accelerated alloy layer growth, a phenomenon known as the Sandelin effect.

Electro-galvanized coatings are much thinner and smoother, making them more compatible with fine tolerances, coatings, and sealants. Their uniform appearance is often preferred in automotive panels, electronics enclosures, and indoor architectural components where aesthetics and tight fits are required.

In zinc-sprayed coatings, surface finish depends on particle size, spray parameters, and surface preparation. These coatings are often porous and require sealing to achieve comparable corrosion resistance to hot-dip methods.

Surface hardness also changes after galvanization. The outer zinc layer is softer than the steel substrate, which improves its sacrificial behavior but limits abrasion resistance. Microhardness of zinc layers typically ranges from 50 to 100 HV, compared to 120–180 HV for low-carbon steel. This softness can cause wear in sliding or contact applications, especially if not protected with secondary coatings.

Adhesion and Coating Uniformity

Uniform coating is critical to ensuring consistent corrosion resistance. In hot-dip processes, achieving uniform thickness is challenging on sharp edges, internal cavities, and recessed features. Zinc tends to drain unevenly, leading to thicker deposits on corners and thinner layers in tight gaps. Poor part orientation during immersion can trap air, resulting in bare spots.

To mitigate this, parts should be designed with proper drainage holes, venting paths, and edge rounding. Geometry plays a decisive role: simple flat plates yield better coating uniformity than complex fabrications with tubes or blind holes.

Electro-galvanizing offers better uniformity, especially on complex geometries, due to the nature of electric field distribution in plating tanks. However, it is more sensitive to surface contamination and current density control.

Coating adhesion depends on metallurgy, not just mechanical bonding. In hot-dip galvanizing, intermetallic layers ensure excellent adhesion, but overgrowth of brittle phases like zeta phase (FeZn13) can reduce impact resistance. In electro-galvanized parts, poor bath chemistry or surface prep may cause delamination under mechanical stress.

In critical applications such as bridges, towers, or utility structures, coating uniformity and adhesion are verified through destructive or non-destructive tests, including peel tests, cross-cut adhesion testing, or microstructural evaluation.

Welding Behavior of Galvanized Steel

Weldability Impact

Welding galvanized steel presents unique challenges that must be addressed to maintain joint integrity and workplace safety. The zinc layer, while beneficial for corrosion resistance, introduces several technical problems during welding due to its low vaporization temperature (~907°C), which is far below the melting point of steel.

When exposed to arc heat, zinc vaporizes rapidly and creates dense white fumes composed primarily of zinc oxide. These fumes are not only hazardous to health but also interfere with weld pool stability. Zinc vapor can cause porosity in the weld bead, reduce fusion between base metals, and leave behind inclusions that weaken the joint.

Moreover, as the zinc burns off, it causes excessive spatter and slag formation, particularly in manual processes like shielded metal arc welding (SMAW) and gas metal arc welding (GMAW). In automated or high-speed robotic welding setups, spatter accumulation can damage equipment and increase downtime.

Thermal decomposition of the zinc layer can also lead to delayed cracking in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) due to hydrogen absorption, especially in high-strength or low-alloy steels. Welders must therefore consider both metallurgical and process-related risks when working with galvanized materials.

Recommended Pre- and Post-Weld Practices

Proper welding of galvanized steel requires a disciplined approach to preparation, technique, and post-treatment.

Before welding, localized removal of the zinc coating is recommended. Grinding or abrasive blasting around the weld area reduces fume generation and improves arc stability. In structural applications, it is common to strip at least 25 mm from each side of the joint line. Chemical stripping is also possible but less common due to environmental and handling concerns.

During welding, use of low-hydrogen electrodes, controlled heat input, and slower travel speeds can help mitigate porosity and cracking. For fillet welds, open root designs and back-gouging may be necessary to ensure complete fusion. Welding sequence should also allow adequate venting to prevent pressure buildup from vaporized zinc, especially in enclosed or tubular structures.

After welding, joint areas should be cleaned of slag and re-coated to restore corrosion resistance. Common post-weld touch-up methods include zinc-rich paint, metallizing, or small-scale hot-dip repair where practical. All repair materials must conform to standards such as ASTM A780 or ISO 1461 Annex C to ensure equivalent protection.

Ventilation is essential during all welding operations on galvanized steel. Local exhaust systems or fume extractors must be used in confined spaces to control worker exposure to zinc oxide fumes and other combustion byproducts.

In critical applications—such as pipelines, transmission towers, or load-bearing bridge components—weld procedure qualification records (PQRs) must specifically account for the presence of zinc coatings. Weld quality testing may include ultrasonic inspection, radiographic examination, or destructive mechanical testing depending on the regulatory or contract requirements.

Wear and Abrasion Resistance

Zinc’s Resistance to Mechanical Damage

While galvanization significantly improves corrosion resistance, its mechanical durability under abrasion is limited. The zinc layer formed by galvanization—particularly in hot-dip processes—is relatively soft compared to the underlying steel. On the Mohs scale, zinc registers around 2.5, whereas carbon steel ranges between 4 and 5.

In environments involving frequent mechanical contact, sliding surfaces, or material impact, the galvanized coating is prone to wearing away. Once the zinc layer is compromised, the exposed steel becomes vulnerable to corrosion, especially in high-humidity or chemically aggressive settings.

Hot-dip galvanization does provide better abrasion resistance than electro-galvanization due to its greater thickness. Thicker coatings, often exceeding 80 µm, offer a longer wear life in applications like utility poles or guardrails. However, even these thicker layers degrade faster under repetitive physical stress.

In contrast, electro-galvanized coatings—though more uniform—are much thinner and often wear through within months if used in high-friction assemblies. Zinc spraying exhibits moderate wear resistance but varies with coating porosity and sealing effectiveness.

Coating Longevity Under Repeated Friction

When evaluating galvanization for use in environments involving vibration, cyclic movement, or contact wear, engineers must consider the long-term integrity of the zinc coating. Examples include conveyor components, bolted flanges, rail hardware, and structural bearings.

Repeated micro-friction can lead to coating erosion, especially at points of concentrated pressure such as bolt heads, edges, or interfaces between mating parts. Surface damage typically starts as polishing or micro-scratching, which progresses into complete exposure of the steel substrate.

Once the protective barrier of the galvanization layer is breached, corrosion advances rapidly. Localized rust formation not only weakens the part but may also expand beneath adjacent zinc-coated areas, lifting or flaking the remaining coating.

To improve performance, secondary treatments may be applied to galvanized parts. These include:

- Organic coatings over galvanized substrates (duplex systems)

- Polymer topcoats for wear-critical areas

- Post-galvanizing heat treatments to improve intermetallic hardness

However, even with post-treatments, galvanization is not suitable for components subjected to continuous mechanical load or abrasive particulate flow, such as slurry pipes or machine bed slides.

For such applications, surface engineering alternatives—like thermal spraying with tungsten carbide, nitriding, or hard chrome plating—offer superior wear protection, though at higher cost and complexity.

Service Life and Environmental Limits

Performance in Outdoor and Marine Conditions

Galvanization is widely selected for outdoor structural applications due to its ability to withstand prolonged environmental exposure. In atmospheric conditions—particularly rural and suburban settings—hot-dip galvanized coatings can provide reliable corrosion protection for 30 to 70 years, depending on coating thickness and local climate.

Zinc’s natural oxidation in air forms a stable, adherent patina composed of zinc carbonate. This passive layer further slows down corrosion by reducing zinc’s reactivity. In dry or temperate zones, this passive film remains intact and effective for decades, making galvanization one of the most economical corrosion prevention methods in civil infrastructure.

However, in marine or coastal environments, galvanization faces accelerated degradation due to chloride-rich aerosols and saltwater spray. These conditions cause the protective zinc layer to break down more quickly. In such settings, coating thickness must be maximized, and duplex protection systems (galvanization plus epoxy or polyurethane topcoats) are often recommended for extended service life.

In industrial zones with high sulfur dioxide concentrations or acidic pollutants, galvanization may also underperform. The zinc coating reacts with these compounds to form soluble zinc salts, which wash away and leave the substrate exposed over time. Engineers must consider the chemical aggressiveness of the atmosphere when selecting galvanization as a protective method.

Degradation Over Time

Galvanized coatings degrade predictably and visibly, which helps in maintenance planning. Initial signs of coating failure include discoloration, white rust, and localized roughening of the surface. Over time, these effects progress to red rust where steel is no longer protected.

White rust—caused by zinc hydroxide formation in poorly ventilated, moist storage—is a common early-stage issue. Though not structurally damaging, its presence indicates poor storage practices and can affect visual inspection outcomes. Storage recommendations for galvanized parts include dry, inclined stacking, breathable covers, and short-term exposure control.

Galvanization’s time-to-failure is directly linked to coating thickness, typically expressed in microns or ounces per square foot. Every 10 µm of zinc thickness roughly equates to one to two years of protection in moderate environments. This allows engineers to specify coating thickness based on expected service duration and exposure class, as defined in ISO 9223 and ASTM A123.

Once zinc is fully consumed, corrosion of the underlying steel accelerates. At this point, the part is functionally compromised, and replacement or extensive repair becomes necessary. Monitoring protocols often include periodic visual inspection, magnetic thickness testing, and corrosion mapping in critical infrastructure.

In cases of partial degradation, remedial actions such as application of zinc-rich paints, cold galvanizing sprays, or re-galvanizing (where practical) may be implemented. However, these repairs are rarely equivalent to original hot-dip coatings in bond strength or durability.

Application Suitability

Where Galvanization Works

Galvanization remains a cornerstone protective strategy in many industrial sectors due to its low cost, proven performance, and ease of implementation. It is particularly effective for components exposed to outdoor, humid, or cyclically wet environments where corrosion is a critical threat.

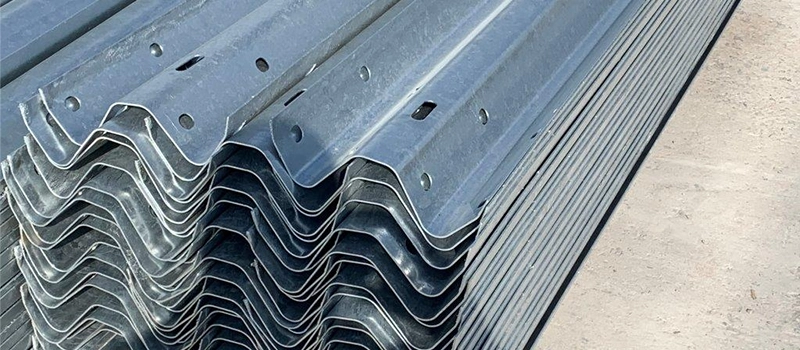

Common applications of galvanization include:

- Structural steel beams and frameworks in buildings and bridges

- Highway guardrails, utility poles, street lighting columns

- Agricultural fencing, greenhouse frames, and irrigation hardware

- HVAC duct brackets, piping supports, and rooftop installations

- Storage tanks, silos, and bins exposed to ambient weather

In these settings, galvanization provides a reliable first line of defense against rust, especially where maintenance access is limited. It is often specified in national building codes, public utility guidelines, and transportation infrastructure standards due to its long-term corrosion performance.

Fasteners—bolts, nuts, and washers—are another major application area, particularly when installed in conjunction with galvanized structures. Standardized systems ensure zinc compatibility across assemblies, minimizing galvanic mismatch and extending joint life.

Additionally, pre-galvanized sheet steel is widely used in HVAC ducting, framing systems, and electrical enclosures, providing cost-effective protection in controlled interior environments.

Where Galvanization Fails or Underperforms

Despite its widespread utility, galvanization is not universally suitable. Its limitations arise primarily from mechanical, thermal, or environmental incompatibilities.

Galvanization is not recommended for components exposed to:

- High abrasion or continuous mechanical wear: Zinc’s softness leads to rapid loss in sliding contacts, chain guides, or moving hinges.

- Elevated temperatures above 200°C: Zinc begins to soften and oxidize more rapidly, degrading protective value and posing fume risks in fire scenarios.

- High-chloride or chemically aggressive environments: In marine atmospheres, chemical plants, or areas with acid rain, zinc reacts unfavorably and deteriorates faster.

- Precision-machined surfaces: The zinc layer’s irregular thickness and micro-crystallinity affect tolerance control, sealing interfaces, or mating surfaces in close-fit assemblies.

Other constraints involve:

- Poor adhesion on certain steels (e.g., reactive grades with high silicon content)

- Welding complications, as discussed earlier

- Limitations in part size: Immersion in hot-dip tanks restricts the size and geometry of components that can be treated

For these scenarios, alternative surface protection methods may be more appropriate. These include powder coating, anodizing (for aluminum), epoxy paints, thermal sprays, or stainless steel selection depending on cost and performance trade-offs.

Design engineers and procurement specialists must evaluate galvanization not as a universal solution, but as one corrosion strategy within a broader material engineering toolbox. Early coordination between design, coating, and fabrication teams is essential to match galvanization’s capabilities to the actual service requirements of the part.

Conclusion

Galvanization offers reliable, cost-effective corrosion resistance for structural and outdoor applications, especially when applied to well-designed, clean steel surfaces. However, its limitations in wear, heat, and chemical exposure must be considered during material selection. Engineers should match galvanization methods to service conditions to avoid premature coating failure.