Choosing the right machining process can be a significant challenge for engineers and procurement teams alike. With multiple options such as turning, milling, drilling, grinding, and EDM available, selecting the most suitable method for a specific metal part often leads to confusion and costly trial-and-error.

An improper machining process choice may result in increased production costs, extended lead times, compromised part quality, or mismatches between design tolerance and actual output. These issues not only affect downstream assembly but can also lead to severe quality control setbacks and customer dissatisfaction in critical industries like automotive, construction, and mining.

This article provides a comprehensive, side-by-side comparison of the five core machining processes, analyzing their advantages and limitations across key performance factors such as precision, material compatibility, cost-efficiency, and scalability. Whether for prototyping or full-scale production, understanding the pros and cons of each machining process is essential for making informed manufacturing decisions.

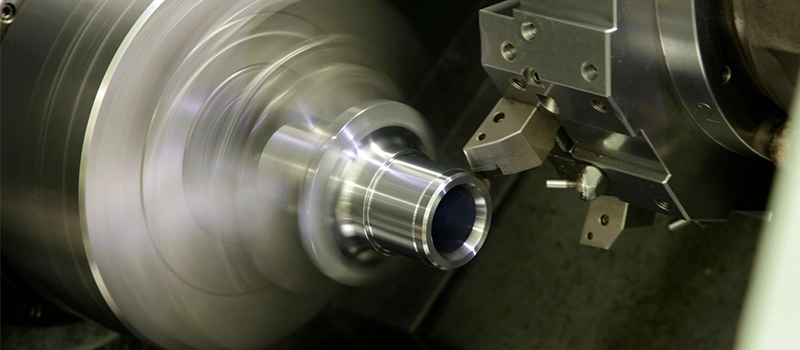

Turning: The Foundation of Rotational Machining

Overview of Turning in Modern Machining

Turning is one of the most fundamental and widely used machining processes in metalworking, especially for manufacturing cylindrical parts. Performed primarily on a lathe, this process involves rotating the workpiece while a stationary cutting tool removes material. It is commonly applied in the production of shafts, bushings, pins, pulleys, and similar round or symmetrical components.

This method is essential for achieving dimensional accuracy in external and internal diameters, and is highly favored in industries like automotive, aerospace, and heavy equipment manufacturing due to its repeatability and cost-efficiency in high-volume production.

Advantages of the Turning Process

- High Precision for Round Components

Turning excels at producing components with tight tolerances, especially in rotational symmetry. The concentricity, roundness, and surface finish achievable make it ideal for high-performance mechanical applications. - Excellent Surface Finish

When paired with proper tool geometry and feed rate, turning can produce a near-polished surface, minimizing the need for secondary finishing processes such as grinding. - Cost-Efficiency in Mass Production

In automated CNC turning centers, this process offers high throughput at relatively low cost per unit. The reduced setup time and fast material removal rate make it one of the most economical solutions for large production runs. - Versatility in Material Types

Turning can be performed on a wide range of materials—from soft aluminum to hardened steel and exotic alloys—provided the correct tool and cutting parameters are selected. - Compatible with Secondary Operations

Operations like threading, grooving, boring, and parting-off can be integrated in a single turning setup, improving overall process efficiency.

Disadvantages of the Turning Process

- Limited to Rotational Parts

Turning is restricted to parts with circular cross-sections. Complex geometries, prismatic shapes, or irregular features cannot be efficiently machined with this method alone. - Potential for Tool Wear and Vibration

In long or slender workpieces, vibration (chatter) can occur, reducing surface quality and accelerating tool wear. Tool life is also sensitive to improper speeds and feeds, especially in hard materials. - Higher Waste for Some Designs

Turning removes material from a solid stock, which can lead to higher material wastage compared to near-net-shape manufacturing techniques like forging or casting. - Limited Multi-Axis Capability

Compared to milling or 5-axis machining, turning offers fewer degrees of freedom in tool orientation. Multi-axis lathes do exist, but they significantly increase capital investment.

When to Choose Turning

Turning should be the process of choice when:

- The part is primarily round in shape

- Dimensional accuracy and smooth surface finish are critical

- The production volume justifies dedicated tooling and setup

- The material is suitable for single-point cutting operations

Engineers and buyers working with rotational components will find turning to be a highly controllable, efficient, and scalable machining process—provided that part design aligns with its geometrical constraints.

Milling: The Workhorse of Complex Geometry Machining

Overview of Milling in Precision Manufacturing

Milling is a versatile machining process that involves the use of rotary cutters to remove material from a stationary workpiece. Unlike turning, where the part rotates, in milling the cutting tool does the rotating, enabling multi-axis movement and a wide range of geometric capabilities. This makes milling ideal for machining flat surfaces, grooves, slots, and complex 3D shapes.

With the widespread adoption of CNC (Computer Numerical Control) technology, milling has evolved into one of the most powerful and adaptable machining methods, essential for mold making, structural parts, and custom component fabrication.

Advantages of the Milling Process

- High Flexibility in Geometry

Milling allows for the creation of intricate profiles, contours, cavities, and surfaces that would be impossible or inefficient to produce with turning. It is well suited for parts with irregular shapes or multiple faces. - Multi-Axis Machining Capability

Modern milling centers—especially 3-axis, 4-axis, and 5-axis machines—provide significant freedom in tool orientation and movement, enabling the production of complex parts in a single setup. - Material Compatibility

This machining process supports a broad range of materials, including metals like steel, aluminum, titanium, and copper, as well as plastics and composites, depending on the tooling. - Excellent Dimensional Accuracy

With the right fixturing, cutting strategy, and toolpath control, milling can achieve precise dimensions and tight tolerances on flat and angled surfaces alike. - Surface Quality and Feature Definition

When used with high-speed spindles and fine stepovers, milling provides sharp edges, smooth transitions, and aesthetically clean surfaces.

Disadvantages of the Milling Process

- Higher Setup Complexity

Compared to turning, milling often requires more complex fixturing, toolpath programming, and workpiece alignment, especially for multi-face operations. - Lower Efficiency for Cylindrical Parts

While capable, milling is not the most efficient method for round components, where turning would typically offer faster cycle times and better concentricity. - Increased Tool Wear on Hard Materials

Milling hard metals or abrasive materials can lead to rapid cutter degradation, requiring more frequent tool changes and monitoring. - Cost Implications of 5-Axis Machines

While multi-axis milling opens up advanced capabilities, the machines are more expensive, and operator skill requirements are significantly higher. - Material Waste

Similar to turning, milling is a subtractive process, and depending on the part design, it can generate a high volume of chips and unused material.

When to Choose Milling

Milling is the optimal machining process when:

- Parts require complex geometries, flat surfaces, or angular cuts

- Multi-face machining is needed in a single setup

- Design tolerances cannot be met by casting or forming alone

- Material removal is acceptable and compensated by part value

For manufacturers handling low to medium batch runs of intricate components, or engineers developing parts with varied surface orientations, milling provides unmatched flexibility and control—making it a cornerstone in modern subtractive manufacturing.

Drilling: The Essential Machining Process for Fast and Accurate Hole-Making

Overview of Drilling as a Core Machining Process

Drilling is a foundational machining process used to create round holes in metal, plastic, and composite materials. It is typically the starting point for many component designs, as drilled holes often serve as the basis for fasteners, alignment pins, and assembly features. The process involves rotating a cutting tool (the drill bit) against the stationary workpiece to remove material.

As one of the most frequently performed operations in any machine shop, drilling is indispensable in nearly all manufacturing industries—from automotive to aerospace and heavy machinery.

Advantages of the Drilling Process

- Fast and Efficient Hole Creation

Drilling is the fastest way to produce straight, round holes with consistent diameters. It is ideal for high-speed production environments where efficiency is paramount. - Supports Secondary Operations

Once a hole is drilled, it can be further refined through other machining processes like reaming, counterboring, tapping (for internal threads), or boring (for tight tolerance finishing). - Low Equipment and Tooling Cost

Drilling machines and drill bits are relatively inexpensive compared to more complex CNC equipment. This makes drilling one of the most cost-effective machining processes in terms of tooling investment. - High Repeatability

With proper fixturing and drill geometry, this machining process offers excellent positional accuracy and repeatability across large production batches. - Wide Range of Sizes and Depths

From micro-holes in electronics to deep bores in structural steel, drilling accommodates a vast range of dimensions with the right bit and feed control.

Disadvantages of the Drilling Process

- Limited to Circular Holes Only

Drilling cannot create non-round shapes or complex hole patterns without additional machining processes. This makes it less flexible for parts with advanced design geometries. - Prone to Burr Formation

Exit burrs are common in drilled holes, requiring secondary deburring operations to maintain clean edges and prevent assembly interference. - Tool Deflection in Deep Holes

As hole depth increases, drill bits are more prone to deflection and misalignment, which can compromise straightness and diameter consistency. - Surface Finish Limitations

Compared to reaming or boring, the surface finish produced by drilling alone is generally rougher, which may not meet final specifications in precision components. - Heat Generation and Chip Clogging

Without proper coolant flow and chip evacuation, drilling can overheat the tool and workpiece, reducing tool life and hole quality.

When to Choose Drilling

Drilling is the most suitable machining process when:

- The primary operation is hole creation for bolts, threads, or alignment

- Cost and speed are more critical than ultra-high surface finish

- The design includes features that will be refined using other processes

- The production volume justifies dedicated drilling setups or CNC cycles

As a core machining process, drilling plays a vital role in both standalone operations and integrated workflows. It is often the gateway to more advanced hole-finishing techniques and remains one of the most universally applied methods in manufacturing today.

Grinding: The Precision Machining Process for Tight Tolerances and Fine Finishes

Overview of Grinding in Precision Engineering

Grinding is a high-precision machining process used to achieve exceptionally fine surface finishes, accurate dimensions, and tight tolerances. Unlike cutting processes that use single-point tools, grinding uses abrasive wheels to wear away material from the surface of a workpiece. This process is most commonly applied after rough machining, serving as a finishing step in the manufacturing workflow.

Used extensively in industries such as aerospace, automotive, mold tooling, and medical devices, grinding is the go-to machining process when dimensional accuracy and surface quality cannot be compromised.

Advantages of the Grinding Process

- Exceptional Dimensional Accuracy

Grinding is capable of producing components within microns of their specified dimensions. It is ideal for applications that demand extreme precision, such as bearing races, valve seats, and gauge components. - Superior Surface Finish

This machining process delivers surface roughness values far better than turning or milling, making it essential for parts that require smooth contact areas, low friction, or high visual appeal. - Ability to Process Hardened Materials

Unlike many other machining processes, grinding can efficiently cut through heat-treated steels, carbides, ceramics, and other extremely hard materials without tool failure. - Tight Control of Geometrical Features

With the right setup, grinding can maintain roundness, flatness, cylindricity, and parallelism across critical surfaces—attributes essential in complex assemblies. - Versatility of Grinding Methods

Surface grinding, cylindrical grinding, internal grinding, and centerless grinding each offer specialized capabilities tailored to different shapes and requirements.

Disadvantages of the Grinding Process

- Slower Material Removal Rates

Compared to turning or milling, grinding removes material more slowly, making it less efficient for roughing or large-volume stock removal. - Higher Equipment and Operating Costs

Precision grinding machines and abrasive wheels are expensive to acquire and maintain. Additionally, operators must be skilled in setup and inspection to ensure consistent quality. - Heat Generation and Thermal Damage

This machining process can generate significant heat, which may alter the metallurgical properties of the workpiece if not properly managed with coolants or heat control techniques. - Limited Suitability for Soft Materials

Softer materials, such as plastics or pure aluminum, can clog the abrasive wheel, reducing its effectiveness and causing surface damage. - Additional Safety Considerations

Grinding wheels operate at extremely high speeds and must be handled with care. Improper mounting or wheel selection can result in catastrophic failure or operator injury.

When to Choose Grinding

Grinding is the preferred machining process when:

- The application requires extremely tight tolerances (under ±0.01 mm)

- The surface finish must be exceptionally smooth (Ra < 0.4 µm)

- The material is too hard or brittle for conventional cutting tools

- A final finishing step is needed after primary machining

As a core machining process, grinding stands out for its ability to deliver unmatched accuracy and surface quality. While slower and more costly, it plays a critical role in high-performance manufacturing where precision cannot be compromised.

EDM: The Specialized Machining Process for Complex and Hard Materials

Overview of Electrical Discharge Machining

Electrical Discharge Machining (EDM) is a non-traditional machining process that removes material using controlled electrical discharges—essentially, sparks—between an electrode and the workpiece, which must be electrically conductive. Unlike turning or milling, EDM does not involve direct mechanical contact, making it ideal for delicate, hard, or complex parts that are difficult or impossible to machine by conventional means.

This advanced machining process includes two main types: sinker EDM, commonly used for cavity shaping (such as in mold-making), and wire EDM, used for precise cutting of intricate profiles and tight corners. EDM plays a vital role in the aerospace, medical, tool-and-die, and precision optics sectors.

Advantages of the EDM Process

- No Mechanical Cutting Force

Because there is no physical contact between the tool and the workpiece, EDM is perfect for machining fragile or thin-walled parts that might deform under mechanical stress. - Ability to Cut Hardened Materials

EDM easily machines through hardened steel, titanium, tungsten carbide, and heat-treated alloys—materials that quickly wear down conventional tools. This makes it a preferred machining process for post-heat-treatment operations. - High Precision and Fine Detail

EDM is capable of producing ultra-tight internal corners, sharp edges, and intricate geometries, especially in wire EDM, where cutting tolerances can reach ±0.002 mm. - Minimal Burr Formation

Unlike mechanical cutting processes, EDM produces little to no burrs, reducing the need for secondary deburring or finishing work. - Excellent Surface Integrity

With proper settings and dielectric fluid management, EDM can deliver fine surface finishes suitable for tooling and sealing applications.

Disadvantages of the EDM Process

- Slower than Conventional Methods

As a material removal method, EDM is relatively slow, especially for large volumes. It’s best suited for low to medium-volume high-precision work. - Limited to Conductive Materials

This machining process only works with electrically conductive materials. Non-metallic or non-conductive parts cannot be machined using EDM. - High Tooling and Operating Costs

EDM requires custom electrodes (for sinker EDM), high-end equipment, and skilled operators. Maintenance of dielectric fluid systems and precision controls also adds to operational costs. - Heat-Affected Zones (HAZ)

While controlled, the spark erosion process introduces localized heating, which may create a thin heat-affected layer that could affect fatigue life in critical applications. - Complex Setup and Programming

Achieving optimal results with EDM often requires detailed CAD/CAM programming, accurate electrode design, and extensive trial runs, especially for new part geometries.

Need Help? We’re Here for You!

When to Choose EDM

EDM is the ideal machining process when:

- The workpiece is made of hardened or exotic alloys

- Sharp internal corners or tight-tolerance features are required

- The part geometry is too complex for milling or turning

- Minimal burr or post-processing is desired

- Surface integrity and finish must meet high specifications

As the most specialized of the five core machining processes, EDM offers unmatched capability for manufacturing components with demanding geometries and material properties. While slower and more expensive, it fills a critical role in precision engineering where other processes reach their limits.

Conclusion

Selecting the right machining process depends on part geometry, material, precision, and production goals. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each core method, manufacturers can make smarter decisions that reduce cost, improve quality, and ensure long-term production success.