Types of machining processes often cause confusion when selecting for precision, tolerance control, or material compatibility. Is your current method failing to deliver dimensional stability or required surface finish?

When the chosen process doesn’t match the material’s thermal behavior or the part’s geometric features, tool degradation, vibration, and rework increase rapidly. As noted in ISO/TR 14638:2010, “process chains must be optimized based on both workpiece properties and performance expectations.” Without alignment, parts fail under inspection or in service.

Understanding how each machining process behaves under load, heat, and stress enables better decisions during manufacturing planning and reduces downstream risk.

What Are Machining Processes?

Definition and Role in Manufacturing

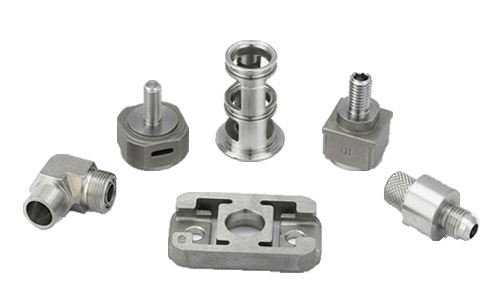

Types of machining processes refer to subtractive manufacturing methods used to remove material from a solid workpiece in order to achieve specific geometric and dimensional outcomes. These processes include operations such as turning, milling, drilling, and grinding. Each method is defined by its tooling configuration, direction of cutting motion, and interaction with the material being machined. Machining is widely applied in sectors such as automotive, aerospace, energy, medical devices, and general industrial equipment.

Machining typically follows forming or casting processes when higher dimensional accuracy, surface finish, or geometric complexity is needed. It allows tolerances in the range of ±0.005 mm and surface finishes as fine as Ra 0.2 µm, depending on the setup. While many parts are cast, forged, or formed near-net shape, machining finalizes critical features such as bearing seats, sealing faces, or threaded holes. CNC-controlled machines can repeat these operations at scale while maintaining uniformity across batches.

In high-precision manufacturing environments, machining is tightly integrated with digital workflows including CAD modeling, CAM programming, and real-time toolpath optimization. Parameters such as feed rate, spindle speed, and tool engagement are calculated based on material behavior, tool life, and heat generation. The role of machining is not only to shape but also to ensure the functional integrity of parts during assembly and in service.

Governing Standards and Technical Expectations

Machining processes are regulated by dimensional and geometric tolerancing standards to ensure that parts produced across different suppliers and regions meet the same functional criteria. These include standards for general tolerances, geometric dimensioning, surface texture classification, and data interoperability across CAD and CAM systems.

These standards guide how tolerances are applied to machined features and how surface finish must meet functional requirements such as oil retention, friction reduction, or sealing contact. Geometric dimensioning and tolerancing defines flatness, perpendicularity, concentricity, and other critical relationships between features that machining must achieve.

Tool selection and cutting conditions must match the material’s machinability index, a value derived from mechanical properties like hardness and tensile strength. For example, free-machining brass is rated high in machinability, while hardened steels or titanium alloys require adjusted speeds and coated tools to reduce tool wear.

Process selection must also reflect how the part will behave in service. This includes how the material responds to thermal input during cutting, how residual stresses affect functional performance, and how surface quality influences wear resistance or fatigue life.

Primary Types of Machining Processes

Turning

Among all types of machining processes, turning is the most common method for producing rotationally symmetric parts. It involves the removal of material from a rotating cylindrical workpiece using a single-point cutting tool. This process is typically carried out on a lathe and is ideal for generating consistent external diameters, internal bores, grooves, and threads.

Turning is applied when high precision is required along the part’s longitudinal axis. Applications include shafts, pins, sleeves, flanges, and connectors where concentricity and roundness are critical. Of all types of machining processes, turning offers excellent control over dimensional accuracy in one axis and surface uniformity across cylindrical profiles.

In practice, the workpiece is secured in a chuck and rotated at a defined spindle speed while the cutting tool moves parallel or perpendicular to the workpiece axis. The feed rate, cutting speed, and depth of cut are determined by the workpiece material, desired finish, and tool geometry. Among types of machining processes, turning demands close attention to tool deflection and vibration, especially when long slender parts are involved.

Turning is compatible with a wide range of metals, including steel, aluminum, copper alloys, and titanium. Materials with poor machinability, such as high-strength stainless steels, require lower cutting speeds and sharper tool geometries. In such cases, coolant flow, chip evacuation, and insert selection directly affect tool life and surface quality.

Modern CNC turning centers support automated tool changes, live tooling for milling or drilling operations, and synchronized spindles for complete machining in one setup. As one of the foundational types of machining processes, turning enables high-volume production of critical parts with repeatable precision.

Milling

Among all types of machining processes, milling is the most versatile for generating complex shapes, slots, pockets, and contoured surfaces. It involves removing material from a stationary workpiece using a rotating multi-point cutting tool. Milling operations can be performed in horizontal or vertical orientations, depending on the machine configuration and part geometry.

This process is preferred when a component requires intersecting features, prismatic geometry, or surface planes with tight flatness and angular control. Of the various types of machining processes, milling enables both roughing and finishing in a single setup, making it suitable for high-mix, low-volume production or mass manufacturing.

The cutter rotates at high speed while the workpiece is clamped to a movable table that allows motion along multiple axes. In 3-axis milling, the tool moves in the X, Y, and Z directions, while advanced setups include 4-axis or 5-axis configurations for machining inclined surfaces and undercuts. Among the types of machining processes, 5-axis milling offers the most geometric freedom and eliminates the need for multiple setups.

Tool selection is driven by the material being machined and the geometry required. End mills, ball nose cutters, face mills, and slot drills are used based on the edge profile, engagement depth, and surface finish specification. Cutting parameters—such as spindle speed, feed per tooth, and step-over—must be carefully optimized to avoid tool wear, thermal distortion, or chatter.

Materials commonly milled include aluminum alloys, mild and hardened steels, stainless steel, plastics, and high-performance alloys. Each material behaves differently during milling, which makes tool coating, coolant strategy, and chip evacuation critical to surface integrity and dimensional accuracy. Compared to other types of machining processes, milling introduces higher lateral forces, which must be accounted for during fixture design.

CNC milling is widely adopted in industries such as aerospace, mold making, medical device production, and energy systems due to its ability to generate repeatable, high-precision parts. When applied correctly, this process contributes significantly to reducing dimensional variation, improving surface quality, and minimizing post-processing.

Get a quote now!

Drilling

Drilling is one of the most essential types of machining processes used to create round holes in solid materials. It operates by rotating a multi-point cutting tool, typically a twist drill, which is fed axially into the workpiece. Among the various types of machining processes, drilling is foundational to part fabrication and assembly, providing through-holes, blind holes, counterbores, and tapped features.

This process is used across virtually all industrial applications, from structural components to mechanical housings. Whether the requirement is for clearance holes, threaded holes, dowel pin locations, or fluid passageways, drilling remains indispensable. While often seen as a basic operation, it requires close control of parameters such as point angle, helix angle, cutting speed, and feed rate to ensure dimensional accuracy and avoid defects like hole ovality, breakout, or drill wander.

Unlike other types of machining processes, drilling has unique challenges due to tool geometry and chip evacuation. As the tool penetrates deeper, chip removal becomes more difficult, especially in ductile materials like aluminum or copper alloys. Peck drilling cycles or through-tool coolant delivery are often used to prevent chip packing, tool breakage, and thermal buildup.

The selection of drill bit material—such as high-speed steel, cobalt, or solid carbide—is based on the machinability of the workpiece. For hardened steels or abrasive composites, coatings like TiAlN or diamond-like carbon extend tool life and improve thermal resistance. Deep-hole drilling, defined as hole depth exceeding ten times the diameter, may require specialized methods such as gun drilling or BTA systems to maintain straightness and surface finish.

Among all types of machining processes, drilling plays a critical role in feature positioning and assembly accuracy. Hole location tolerance and perpendicularity directly impact alignment, torque performance, and sealing integrity. Post-drilling operations like reaming, countersinking, or tapping are often integrated into CNC cycles for functional hole finishing.

In production environments, drilling is performed on vertical machining centers, dedicated drill presses, or automated multi-spindle units depending on throughput requirements. The simplicity of setup combined with its functional importance makes drilling a core element of any machining process selection strategy.

Grinding

Grinding is one of the precision-focused types of machining processes used to achieve tight dimensional tolerances and superior surface finishes. It removes material using an abrasive wheel rather than a sharp cutting edge, making it ideal for hard metals and heat-treated components where conventional cutting tools are less effective.

Among various types of machining processes, grinding is most commonly used in the final stage of manufacturing. Its ability to correct form errors, remove small stock amounts, and deliver micro-level flatness makes it suitable for components such as bearing journals, valve seats, die blocks, and precision guides. The process is also used for deburring and surface conditioning after prior operations like turning or milling.

Grinding introduces high contact pressures and localized heat. To avoid surface burns, thermal distortion, or metallurgical damage, wheel composition, speed, feed, and coolant flow must be strictly controlled. Abrasive types include aluminum oxide, silicon carbide, CBN (cubic boron nitride), and diamond, selected based on workpiece hardness and material response.

There are several subtypes of grinding processes, each classified under the broader category of types of machining processes. These include:

- Surface grinding for flat surfaces and faces

- Cylindrical grinding for external and internal round features

- Centerless grinding for parts without a center point

- Creep feed grinding for high material removal at slow feed rates

In most applications, grinding improves not only geometry but also functional characteristics such as friction, fatigue resistance, and sealing effectiveness. The resulting surface finish can reach values as low as Ra 0.05 µm, far beyond what other types of machining processes typically achieve.

Grinding machines may be standalone or integrated into multi-process systems. They are commonly used in industries requiring high repeatability and close dimensional control, including aerospace, toolmaking, and precision bearing manufacturing.

Secondary and Advanced Machining Methods

Some types of machining processes extend beyond traditional mechanical cutting. These advanced methods apply thermal, electrical, or chemical energy to remove material from workpieces that are difficult to machine using conventional tools. Secondary and non-contact processes are especially useful when dealing with hardened materials, intricate geometries, or features that cannot be accessed by standard tools.

In modern manufacturing, secondary types of machining processes are used when tighter tolerances, minimal mechanical force, or tool access constraints exist. These methods are often employed after casting, forging, or additive manufacturing to finish complex surfaces or produce non-standard features. Their integration into the production chain depends on material properties, energy input requirements, and functional constraints.

EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining)

EDM is a thermal-based process that removes material using a series of controlled electrical discharges between an electrode and the conductive workpiece. Of all types of machining processes, EDM is unique in that it does not rely on mechanical force, making it well-suited for delicate or hard-to-machine components.

The process requires an electrode—typically made from graphite, copper, or brass—and a dielectric fluid to facilitate spark generation and debris removal. Material is eroded from the surface in small amounts through localized melting and vaporization. Because there is no direct contact between the electrode and the workpiece, EDM eliminates mechanical stress, tool deflection, and vibration-related errors.

EDM is highly effective for producing sharp internal corners, narrow slots, and fine cavities that are otherwise impossible with rotary tools. It is frequently used for injection molds, punch and die components, turbine blades, and aerospace features made from hardened tool steels, titanium, or carbide alloys.

There are two primary types of EDM within the broader classification of types of machining processes:

- Sinker EDM: Uses a shaped electrode to form complex cavities in 3D profiles

- Wire EDM: Uses a continuously fed wire to cut 2D contours with extremely high precision

Despite its capabilities, EDM is relatively slow compared to mechanical cutting and generates a recast layer that may require post-processing. Electrode wear, dielectric cleanliness, and flushing conditions directly affect dimensional control and repeatability.

EDM stands apart from other types of machining processes by enabling precise material removal in tight spaces, especially in parts that require minimal distortion and consistent geometry without inducing thermal or mechanical loads across the bulk material.

Laser Cutting

Laser cutting is one of the thermally-driven types of machining processes that uses a concentrated beam of light to remove material through melting, burning, or vaporization. It is most commonly applied to sheet metals, plate stock, and thin-walled profiles where precise edge quality and minimal mechanical stress are required.

The laser beam is focused to a narrow spot with extremely high energy density. When directed at the workpiece surface, it generates localized temperatures sufficient to melt or vaporize the material. An assist gas—typically oxygen, nitrogen, or air—is used to clear the molten zone and improve kerf quality. Among all types of machining processes, laser cutting offers some of the narrowest kerfs and lowest thermal distortion when parameters are properly optimized.

Laser cutting is widely used for carbon steel, stainless steel, aluminum, and non-ferrous metals. The process is highly controllable through CNC systems, enabling complex 2D profiles, cutouts, and fine features to be machined without the need for tooling or fixturing. It is especially valuable in prototype production, sheet metal fabrication, enclosure manufacturing, and high-mix, low-volume workflows.

Compared to mechanical types of machining processes like milling or punching, laser cutting produces cleaner edges with reduced burr formation and minimal tool wear. However, its performance is constrained by material reflectivity, thickness, and heat sensitivity. Highly reflective materials such as copper or brass may require specialized fiber laser sources, while thick-section cutting can result in wider heat-affected zones and potential microcracking.

Types of laser cutting include:

- CO₂ lasers: Used for non-metallics and thick sheet metals

- Fiber lasers: Efficient for metals, especially thin stainless steel and aluminum

- Ultrashort pulse lasers: For micro-machining and high-precision cuts in sensitive materials

As one of the non-contact types of machining processes, laser cutting excels in applications where tool access is limited, part deformation must be avoided, or surface finish is critical. However, careful control of focus, feed rate, and gas composition is essential to avoid surface oxidation, tapering, or thermal stress.

Waterjet Cutting

Waterjet cutting is one of the non-thermal types of machining processes that removes material using a high-pressure jet of water, often mixed with abrasive particles. Unlike thermal methods such as laser cutting or EDM, waterjet cutting introduces no heat into the workpiece. This makes it especially useful for temperature-sensitive materials, composite structures, and parts where heat-affected zones are unacceptable.

The process operates by accelerating water up to 3,800 bar (55,000 psi) through a small-diameter nozzle, creating a focused stream capable of eroding material on contact. For metals and hard materials, abrasives like garnet are introduced into the water stream to enhance cutting ability. Among all types of machining processes, waterjet cutting offers unmatched versatility across metals, ceramics, glass, rubber, plastics, and laminated materials.

One of the primary benefits of waterjet cutting is the absence of thermal distortion, phase change, or microstructural alteration. This makes it suitable for aerospace components, architectural elements, and precision parts where dimensional stability and material integrity are essential. Edge quality is generally good, with minimal taper and burr, though post-processing may be required for tight-tolerance applications.

Compared to other types of machining processes, waterjet cutting does have limitations. The process is relatively slower than mechanical or laser methods, particularly on thick or dense materials. It also requires significant infrastructure for water recycling, abrasive handling, and pump maintenance. Additionally, kerf width is larger than that of laser cutting, and surface finish is affected by nozzle wear and standoff distance.

Waterjet cutting systems are controlled via CNC and can accommodate intricate geometries, internal cutouts, and nested parts from flat stock. The process supports both prototype work and full-scale production, particularly in industries like defense, shipbuilding, and custom fabrication where material diversity and part complexity are high.

As one of the most flexible types of machining processes, waterjet cutting offers a low-risk, high-integrity method for precision part fabrication without thermal interference or mechanical loading.

Ultrasonic Machining

Ultrasonic machining is one of the non-traditional types of machining processes that uses high-frequency mechanical vibrations to facilitate material removal. It is especially effective for brittle, hard, or non-conductive materials such as ceramics, quartz, hardened steels, and glass—materials that typically resist conventional cutting methods.

In ultrasonic machining, a tool vibrating at frequencies around 20,000 Hz is pressed against the workpiece while a slurry containing fine abrasive particles flows through the contact zone. Material removal occurs as the abrasives, energized by the vibrating tool, micro-fracture and erode the work surface. Among all types of machining processes, ultrasonic machining stands out for its ability to shape difficult materials without introducing thermal stress or electrical energy.

The process is best suited for small, intricate features such as micro-holes, slots, contours, and blind cavities. Because it is non-thermal and non-chemical, ultrasonic machining does not alter the microstructure of the material. This is critical in applications involving advanced ceramics or composites, where structural integrity and thermal insulation properties must remain unchanged.

While not as fast as mechanical or laser-based types of machining processes, ultrasonic machining offers precise control over geometry and surface quality in challenging materials. Tool wear is minimal compared to EDM or grinding, and because the tool does not rotate, complex internal profiles can be generated without deflection or chatter.

Key factors affecting performance include vibration amplitude, abrasive concentration, slurry flow rate, and tool geometry. The process is typically used for machining hard materials with low ductility and high compressive strength, where edge chipping and thermal cracking must be avoided. Common industries include aerospace, semiconductor, medical device, and electronics packaging, where precision and material compatibility are critical.

As one of the specialized types of machining processes, ultrasonic machining offers a low-force, precision alternative when mechanical cutting is impractical or when maintaining material integrity is the primary constraint.

Process Behavior Under Load

Types of machining processes respond differently under thermal and mechanical stress. During cutting, heat and force affect tool wear, surface finish, and dimensional accuracy. Understanding this behavior is essential for selecting appropriate feeds, speeds, and cooling strategies.

Heat Generation and Stress Zones

Heat is generated in all types of machining processes due to friction and material deformation. High temperatures can distort dimensions, alter surface hardness, or introduce residual stress. Turning distributes heat through the chip and tool, while grinding and EDM concentrate it at the surface.

Processes like laser cutting produce heat-affected zones, while waterjet and ultrasonic machining avoid thermal impact altogether. Heat control is managed through cutting fluids, tool coatings, and energy regulation. Without it, part distortion and tool failure are likely.

Chip Formation and Tool Wear

Chip formation is a defining factor in all types of machining processes. Chips carry heat away from the cutting zone but also reveal material behavior. Continuous chips often indicate ductility, while segmented or brittle chips suggest hard or abrasive materials.

Poor chip control increases tool wear and surface defects. Built-up edges, chip packing, or uncontrolled flow can damage both tool and part. Tool wear modes include flank wear, crater wear, and chipping—each influenced by feed rate, cutting speed, and material hardness.

Among types of machining processes, milling and turning generate shear-type chips, while drilling and grinding require active chip evacuation. Tool life is extended by proper geometry, coatings, and coolant strategy.

Material Removal Rates and Tolerance Stack-Up

Material removal rate (MRR) influences productivity and tool loading across all types of machining processes. Higher MRR increases throughput but also raises heat, vibration, and tool wear. Processes like milling and drilling balance MRR against surface finish and dimensional control.

Tolerance stack-up becomes critical in multi-step machining. Each operation introduces variation that can accumulate, leading to misalignment or fitment issues. Fixture design, in-process inspection, and tight machine calibration reduce cumulative error.

Among types of machining processes, high-speed methods improve efficiency, but precision demands may require slower cuts or finishing passes. Matching process speed to tolerance requirements is essential for stable production.

Manufacturing and Inspection Considerations

Types of machining processes are only effective when paired with suitable equipment and verification methods. Machine capability, part fixturing, and inspection strategy must align with tolerance, material, and geometry requirements to ensure reliable output.

Machine Tool Compatibility

Not all types of machining processes are compatible with every machine tool. Turning requires rotational spindles, while milling depends on multi-axis table movement. EDM, laser, and waterjet systems need specialized energy delivery setups and environmental controls.

Machine rigidity, axis resolution, spindle speed range, and tool changer capacity must match process demands. For example, high-speed milling requires vibration damping and thermal stability, while grinding needs controlled axis backlash and fine feed resolution.

Choosing the wrong machine for a given process leads to tolerance drift, surface defects, or premature wear. Matching the type of machining process to machine capability is essential for consistent production and repeatable results.

Surface Finish Expectations

Surface finish varies across different types of machining processes. Turning and milling produce visible toolpath marks, while grinding and EDM create smoother finishes with minimal texture. Selection depends on application needs—such as sealing, wear resistance, or fatigue performance.

Factors Influencing Surface Finish

- Tool geometry and condition: Worn tools degrade surface integrity

- Cutting parameters: Low feed and shallow depth improve finish

- Material properties: Harder materials often yield better finishes

- Machine vibration: Poor damping leads to chatter and patterning

- Coolant/lubrication: Reduces friction and flushes chips

Finish Ranges by Process Type

- Turning: Ra 1.6–3.2 µm (typical)

- Milling: Ra 0.8–1.6 µm with fine tools

- Grinding: Ra 0.2–0.8 µm

- EDM: Ra 0.3–0.8 µm (depends on settings)

If surface finish is critical, secondary processes like lapping or polishing may be used. Among all types of machining processes, grinding remains the most reliable for high finish consistency.

Conclusion

Types of machining processes must be selected based on part function, material behavior, and manufacturing constraints. When matched correctly, they ensure dimensional stability, surface performance, and process reliability across production runs.