Soldering is often overlooked in metal fabrication, especially in operations focused on casting. Yet, in many manufacturing environments, it serves a critical purpose: enabling precise, low-temperature joining of metal components after the casting stage. For assemblies that involve small, delicate features or require post-processing connections, soldering offers an effective solution that complements the casting process rather than replacing it.

Unlike welding or brazing, soldering uses filler metals with low melting points, typically under 450°C. This means the base metal—often a cast component—remains unaffected by thermal distortion. It is especially valuable when working with non-structural joints, fittings, electronics, or lightweight assemblies derived from castings. While not suitable for heavy-load applications, soldering is widely used in areas where cleanliness, accuracy, and material preservation matter.

As noted in various international manufacturing standards, including guidelines from organizations such as the International Institute of Welding (IIW) and the American Welding Society (AWS), soldering plays a well-defined role in fabrication workflows. It is particularly relevant when high-temperature joining methods could compromise surface integrity or dimensional accuracy of cast parts. Properly executed, soldering enhances production efficiency and functional reliability, especially in final-stage assembly and precision work.

Applications and Advantages of Soldering in Casting Workflows

Soldering is not a replacement for casting, but a valuable complement to it—particularly during the final stages of component assembly, modification, or repair. In modern manufacturing, especially in multi-process environments, soldering allows manufacturers to create connections between cast parts and other metal components without exposing the base material to high heat or distortion.

Where Soldering Fits After Casting

In practical terms, soldering is commonly applied to cast components when:

- Minor attachments or fittings must be joined post-casting

- Lightweight brackets, terminals, or contact points are added

- Parts require electrical conductivity between joined surfaces

- Aesthetics and clean joint appearance are important

- Heat-sensitive features would be damaged by welding

This makes soldering useful in a wide range of cast component applications—from small industrial valves to HVAC connectors and electronic enclosures that involve cast aluminum or zinc.

Advantages in Low-Temperature Assembly

One of soldering’s greatest advantages in a casting workflow is that it occurs at much lower temperatures—typically below 450°C. This avoids melting or warping the base metal, which is critical when dealing with thinner castings or parts with precision-machined surfaces. The risk of dimensional changes, internal stress, or oxidation is significantly reduced compared to welding.

In addition, soldering allows for easy rework. If a connection is made incorrectly, it can be removed and redone with minimal impact to the cast part. This makes soldering ideal for prototype builds, low-volume custom work, or repairs that occur after casting or machining.

Clean Joints for Non-Structural Needs

Because soldering leaves minimal residue and does not require grinding or polishing, it is often favored for visible or finished surfaces. In cast product assembly—such as decorative fixtures or aluminum housing components—soldering achieves a clean bond line without secondary finishing, reducing production steps and improving final product appearance.

How Soldering Compares to Welding and Brazing for Cast Parts

Soldering, welding, and brazing are all methods used to join metal components, but each process has specific characteristics that make it more or less suitable for different situations. When working with cast parts, the choice between them depends on factors such as heat sensitivity, joint strength requirements, and the type of materials being used.

Each method uses a filler material, but they differ in process temperature, the effect on the base metal, and the strength of the resulting joint. Understanding these differences helps engineers and buyers choose the most appropriate joining method in casting-related workflows.

Temperature and Impact on Cast Materials

Soldering: Low-Temperature, Low Risk

Soldering occurs at temperatures below 450 degrees Celsius and does not melt the base metal. This makes it especially well-suited for joining cast parts that are thin-walled, heat-sensitive, or finished to tight tolerances. Because soldering applies minimal thermal stress, it helps preserve the dimensional accuracy of cast components.

Brazing: Moderate Heat with Better Strength

Brazing operates in a mid-temperature range, typically between 450 and 850 degrees Celsius. While it does not melt the base metal, it applies more heat than soldering and can cause moderate thermal stress. This method is better suited for parts that require greater strength but can still tolerate some heat exposure without warping or cracking.

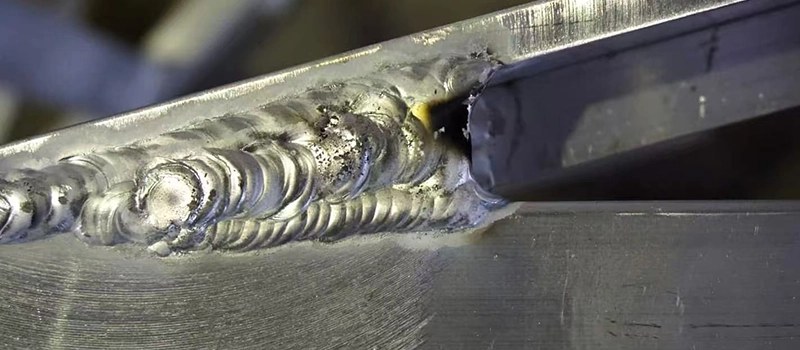

Welding: High-Temperature, High Impact

Welding involves melting both the base material and filler, creating a fully fused joint. This process delivers the strongest mechanical bond but also introduces the most heat. Cast parts, especially those with complex geometry or specific alloy compositions, may be at risk of cracking or internal stress unless welded with proper procedures such as preheating or post-weld heat treatment.

Joint Strength and Mechanical Performance

Soldering: Acceptable for Light-Duty Applications

Soldered joints are generally weaker than those produced by brazing or welding. They are suitable for light-duty or non-load-bearing connections such as electrical terminals, decorative assemblies, or covers on cast enclosures. Their strength is usually sufficient when the joint is not subjected to vibration, tension, or impact.

Brazing: Balanced Performance

Brazed joints are stronger than soldered ones and are used where light structural strength is needed. This makes them appropriate for joining cast parts used in assemblies that face moderate mechanical loads but not severe stress or shock.

Welding: High Structural Strength

Welded joints are the most durable and are typically used when a permanent, high-strength connection is required. In cast components that are part of structural or load-bearing assemblies, welding is often necessary. However, careful control of welding parameters is essential to prevent defects like porosity or cracking, particularly in cast iron or high-silicon aluminum alloys.

Suitable Applications by Joining Method

Ideal Uses for Soldering in Casting

- Precision assembly of cast electrical enclosures or terminals

- Decorative cast components where clean joints are preferred

- Joining small fittings or low-stress parts without thermal damage

Ideal Uses for Brazing in Casting

- Joining cast parts to dissimilar metals

- Creating moderately strong joints without full fusion

- Situations where capillary flow can aid in assembly

Ideal Uses for Welding in Casting

- Structural castings exposed to high mechanical loads

- Pressure-rated components or parts requiring full joint penetration

- Rebuilding or repairing large castings with critical performance requirements

Limitations of Soldering in Structural or Load-Bearing Uses

While soldering is effective for specific applications involving cast components, it is not suitable for every situation. Its low operating temperature and limited joint strength make it unsuitable for parts that must withstand significant mechanical stress, dynamic loads, or prolonged exposure to harsh environments.

Understanding these limitations helps manufacturers and buyers determine when soldering is appropriate—and when it is not.

Limited Mechanical Strength

Not Suitable for High-Stress Joints

Soldered joints are relatively weak in tension, shear, and fatigue resistance. They are not designed to carry weight or resist heavy mechanical loads. In applications such as load-bearing arms, pressure vessels, or rotating assemblies, a soldered connection would fail under operational conditions. These types of parts are better joined using welding or, in some cases, brazing.

Vulnerable to Vibration and Thermal Cycling

Soldered joints may degrade over time if exposed to continuous vibration or changes in temperature. This is due to the soft nature of most solder alloys, which can crack or deform under repeated stress. In cast assemblies used in automotive, industrial, or outdoor equipment, soldering may not offer the required durability.

Joint Reliability Depends Heavily on Preparation

Surface Cleanliness Is Critical

One of the most common reasons for weak or failed soldered joints is poor surface preparation. For a soldered connection to hold, the mating surfaces must be free of oxidation, oil, dirt, and casting residue. This can be difficult to achieve on certain cast surfaces, especially those with porous or rough finishes.

Inconsistent Results in Manual Processes

Soldering often relies on manual labor or operator technique, especially in small-scale operations. Without proper training and temperature control, cold joints or incomplete bonding can occur. Inconsistent application can lead to quality variation, which is problematic in production environments that require process repeatability.

Not Recommended for Safety-Critical Parts

Risk of Failure Under Unexpected Load

Even when correctly applied, soldered joints can fail if unexpected loads are applied. In critical applications such as structural brackets, suspension components, or support housings made from cast materials, a soldered connection does not provide sufficient safety margin. Failure in these scenarios can lead to costly repairs or safety risks.

Limited Use in Regulatory Applications

Certain industry standards—such as those governing construction, transportation, or pressure systems—do not accept soldered joints for structural applications. This further limits soldering’s use in projects requiring certified compliance or traceable quality documentation.

Quality Considerations When Soldering Cast Components

Soldering may not be suitable for every application, but when correctly applied, it can provide reliable, clean joints in cast assemblies. Achieving this reliability depends on a few critical factors—most of which relate to surface condition, process control, and inspection. Poor soldering can result in costly failures, while well-controlled soldering enhances quality and functionality.

Surface Preparation and Material Compatibility

Importance of Clean, Oxide-Free Surfaces

Soldering relies on proper wetting of the solder onto the base metal. If the surface of the casting is oxidized, contaminated, or uneven, the solder will not bond effectively. This is especially important in aluminum castings, which form a thin oxide layer quickly when exposed to air. Cleaning methods such as light abrasion, chemical flux, or pre-tinning can help improve solderability.

Choosing the Right Filler Metal

Not all solder alloys are compatible with every casting alloy. For example, lead-free solders with added silver or tin may be required when working with aluminum castings. Selecting a solder that matches the chemical and thermal properties of the base metal reduces the chance of poor joint formation or corrosion over time.

Controlling the Soldering Process

Temperature Management and Heat Input

Excessive or insufficient heat can both cause problems during soldering. If the joint is overheated, it may damage surface coatings or warp nearby cast features. If underheated, the solder may not flow properly, resulting in a cold joint. Using a temperature-controlled soldering iron or station ensures more consistent results, particularly in repetitive production tasks.

Flux Application and Residue Removal

Flux is essential for cleaning the metal surface during soldering, but it must be applied in the correct amount and removed after the process. Residual flux can cause corrosion or electrical leakage in the long term, especially in assemblies exposed to moisture or vibration. Using no-clean flux or conducting a thorough post-solder cleaning step is recommended in most production environments.

Inspection and Testing Methods

Visual Inspection for Common Defects

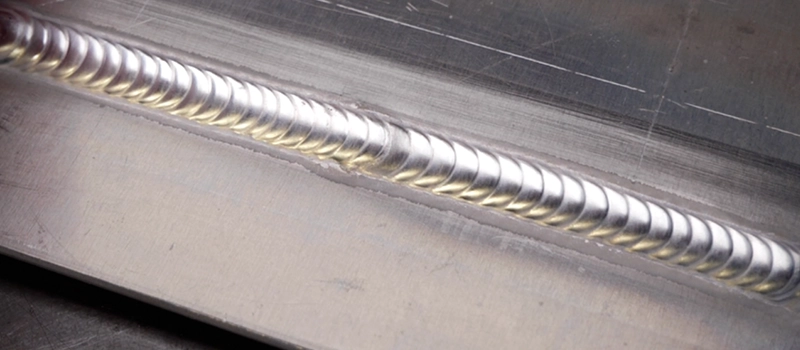

Visual inspection remains the first line of quality control. Signs of a poor solder joint include dull or cracked surfaces, gaps between components, or uneven solder coverage. A good soldered joint should have a smooth, slightly concave shape with full wetting along the contact surfaces.

Functional Testing and Standards

Depending on the application, soldered joints may also undergo mechanical or electrical testing. For example, in cast enclosures containing electrical connections, continuity or resistance testing is used to confirm the joint’s functionality. For precision work, guidelines such as IPC-A-610 (for electronic assemblies) provide detailed standards for acceptable solder joint formation.

Documentation and Supplier Accountability

When soldering is part of the final assembly or repair process, manufacturers should document the materials and methods used. Buyers sourcing cast components that include soldered features should request process control records or certificates of conformance where applicable. This helps ensure consistent quality and builds long-term trust between supplier and customer.

Conclusion

Soldering is not a replacement for casting, but a practical and efficient companion process. When used correctly, it offers a clean, low-heat method for assembling, modifying, or repairing cast components. By understanding its advantages, limitations, and quality requirements, manufacturers and buyers can apply soldering where it truly adds value—without compromising the integrity of the cast part.