How did copper become one of the most essential metals in human history? Why did early civilizations value copper long before iron and steel? And how did the history of copper evolve from primitive tools to modern industrial systems that shape today’s technology and global trade?

The history of copper is inseparable from the history of human civilization itself. From its early discovery and simple tooling to large-scale mining, alloy development, and industrial applications, copper has continuously driven technological progress and economic growth. In this article, I present a clear, structured, and authoritative overview of how copper evolved across different eras—linking ancient innovation with modern industry.

By understanding copper’s past, we can better explain its present value—and anticipate its critical role in future industrial and sustainable development.

The Discovery of Copper and Copper Alloys: Origins of Early Metallurgy

The history of copper begins with direct human interaction with native metals, long before formal science or written language existed. From my professional perspective, copper occupies a unique position in material history because it represents the first metal that humans could recognize, manipulate, and intentionally apply without complex technology.

Copper’s natural occurrence in metallic form distinguished it from most other elements. Early humans encountered copper as visible, malleable nuggets exposed on the earth’s surface. This accessibility explains why copper entered human use far earlier than iron or aluminum. In examining archaeological records, it becomes clear that the copper history of discovery was driven by observation rather than theory.

Early Recognition and Practical Use of Native Copper

In the earliest stages of the history of copper, humans relied on stone tools to cold-hammer native copper into simple shapes. This process required no smelting and no understanding of chemistry. It relied purely on mechanical force and experimentation. Awls, hooks, cutting edges, and basic ornaments made from copper appeared in multiple regions independently, confirming copper’s universal appeal as a workable material.

From a materials standpoint, copper offered several advantages. It was softer than stone but far more durable. It resisted corrosion. It could be reshaped repeatedly without fracturing. These characteristics made copper an ideal transition material between the Stone Age and true metallurgy. This period represents the foundation of history of copper tooling, where form and function began to merge.

The early adoption of copper was not accidental or symbolic alone. It represented a practical improvement in efficiency. Communities using copper tools could process hides, wood, and food resources more effectively. Over time, this functional advantage increased demand, pushing societies toward intentional extraction and the earliest forms of history of copper mining.

The Experimental Path Toward Copper Alloys

As copper use expanded, early metalworkers began to observe a critical limitation: pure copper, while workable, lacked sufficient hardness for certain tasks. This realization marks a decisive moment in the history of copper element—the transition from metal use to metallurgical innovation.

Through repeated heating, mixing, and trial-based experimentation, early craftsmen discovered that combining copper with other naturally occurring metals altered its mechanical properties. This was not scientific alloy theory as we understand it today. It was empirical knowledge built through failure and refinement. The resulting materials were harder, more durable, and better suited for tools and weapons.

This stage represents the true beginning of alloy metallurgy and an essential chapter in the history of the element copper. The discovery that copper could be intentionally modified expanded its value far beyond decorative or light-duty use. It became a structural material capable of supporting complex human activity.

Bronze as a Technological Breakthrough

Among early copper alloys, bronze stands as the most significant development. By combining copper with tin or arsenic, early metallurgists produced a material with superior hardness, edge retention, and casting capability. From my perspective, this innovation transformed copper from a useful metal into a strategic one.

Bronze allowed for standardized production. Tools and implements could now be cast rather than hammered. This enabled greater consistency, improved performance, and wider distribution. The emergence of bronze fundamentally redefined the brief history of copper, extending its influence from individual craftsmanship to organized production systems.

Importantly, bronze did not replace copper. Instead, it expanded copper’s application range. Pure copper continued to be used where flexibility and corrosion resistance were required, while bronze served tasks demanding strength and durability. This complementary relationship reinforced copper’s central role in early technological development.

Metallurgy as a Controlled Process

The combined discovery of copper and copper alloys marks the transition from opportunistic material use to controlled metallurgical practice. Early furnaces, molds, and refining techniques emerged from this period, laying the groundwork for systematic metal production. These developments solidified copper’s status as a foundational industrial material long before the concept of industry formally existed.

When we examine the history of copper at this stage, one conclusion is unavoidable: copper was not merely discovered—it was understood, adapted, and improved. This ability to modify material properties through intentional processes represents one of humanity’s earliest forms of applied engineering.

Copper in Ancient Civilizations: Egypt, Mesopotamia, and Beyond

When examining the history of copper, ancient civilizations represent the first stage at which copper evolved from a useful material into a structured economic and technological resource. From my perspective, this phase is critical because it demonstrates how copper became embedded in administration, craftsmanship, religion, and early industrial organization.

Unlike the experimental phase of early copper use, ancient civilizations applied copper systematically. Mining, refining, tooling, and distribution were no longer isolated practices. They were integrated into social systems. This transformation marks a defining chapter in the history of copper mining and the broader history of the element copper.

Copper in Ancient Egypt: Material, Symbol, and System

In ancient Egypt, the history of copper is closely tied to state organization and monumental construction. Copper tools were widely used for stone working, woodworking, and agricultural equipment. Chisels, saws, drills, and cutting tools made from copper supported large-scale building projects that demanded consistency and durability.

From a materials standpoint, Egyptian metalworkers demonstrated advanced understanding of copper refinement. Smelting techniques improved over time, allowing for more controlled production. This refinement process contributed directly to the expanding history of copper tooling, where standardized shapes and functions became common.

Copper also carried symbolic and economic significance. It was associated with life, protection, and divine power. Copper objects were frequently placed in tombs, reinforcing its perceived permanence. This cultural role strengthened copper’s value beyond utility and helped stabilize demand across generations, an important factor in the long-term history of copper prices.

Mesopotamia: Copper as an Economic Driver

In Mesopotamia, the history of copper followed a different trajectory. The region lacked abundant native copper deposits, which forced early societies to develop long-distance trade networks. This scarcity transformed copper into a strategic import rather than a locally sourced material.

From my analysis, this is one of the earliest examples of copper shaping economic behavior. Copper ore and finished copper products moved across vast distances, linking mining regions with urban centers. This trade-based model significantly influenced the price history of copper, as supply constraints and transportation costs directly affected value.

Copper in Mesopotamia was widely used in tools, weapons, household goods, and administrative objects such as seals and weights. This broad application range reinforced copper’s role as a foundation of daily life. The history of copper element here reflects not innovation alone, but dependence—copper became indispensable.

The Expansion of Copper Use Across Regions

Beyond Egypt and Mesopotamia, the history of copper extends into regions such as Anatolia, the Indus Valley, and early European societies. While techniques differed, the underlying pattern remained consistent. Wherever copper was accessible, societies incorporated it into production, governance, and trade.

What distinguishes this stage in the brief history of copper is scale. Copper production was no longer experimental or local. It was organized. Mining sites expanded. Smelting workshops became permanent. Tool specialization increased. These developments collectively advanced the history of copper mining into a recognizable industrial activity.

In many regions, copper also facilitated early writing systems and measurement standards. Copper plates, rods, and tools were used in construction planning and land management. This functional integration highlights copper’s role in administrative efficiency, not just craftsmanship.

Technological Consistency and Knowledge Transfer

One of the most important aspects of copper in ancient civilizations is the transfer of metallurgical knowledge. Techniques for smelting, alloying, and shaping copper spread through trade routes and cultural exchange. This transmission accelerated the global history of copper, ensuring that improvements in one region influenced others.

From a professional viewpoint, this period represents the stabilization of copper as a technological constant. While designs evolved, copper itself remained central. Its properties were understood, trusted, and relied upon. This reliability is why copper maintained relevance across centuries, even as societies rose and fell.

When we evaluate the history of copper in ancient civilizations, a clear conclusion emerges: copper was not simply used—it was institutionalized. It became part of economic planning, labor specialization, and technological identity. This institutional role explains copper’s uninterrupted presence throughout human history.

The Role of Copper in the Bronze Age

In the history of copper, the Bronze Age represents the first period in which copper became the structural backbone of technological systems rather than a supportive material. From my professional perspective, this stage marks the moment when copper-based metallurgy reshaped production efficiency, labor organization, and material standards across vast regions.

The Bronze Age did not diminish the importance of copper. On the contrary, it amplified it. Bronze itself was impossible without copper. This fact alone places copper at the center of Bronze Age development and secures its position as a defining material in the history of the element copper.

Copper as the Foundation of Bronze Technology

Bronze is, by definition, a copper-based alloy. This simple reality is often overlooked in simplified narratives of early metallurgy. When analyzing the history of copper, it becomes clear that the Bronze Age was not an era of replacement, but one of expansion. Copper remained the primary material input, while alloying techniques enhanced its performance.

From a materials science standpoint, copper provided ductility, corrosion resistance, and workability. Tin or arsenic contributed hardness and strength. Without copper’s stable and predictable behavior, bronze casting would not have been possible at scale. This interdependence reinforces copper’s central role in the brief history of copper during this era.

Copper production therefore increased dramatically. Mining sites expanded. Smelting operations became more specialized. The history of copper mining during the Bronze Age reflects a shift from small-scale extraction to organized, labor-intensive systems capable of supporting growing populations.

Standardization and Mass Production

One of the most important contributions of copper during the Bronze Age was its role in standardization. Because copper could be melted, poured, and cast repeatedly, tools and weapons could be produced in consistent shapes and sizes. This represented a major departure from earlier hand-hammered methods.

In my assessment, this standardization is a critical milestone in the history of copper tooling. Axes, blades, chisels, and agricultural implements became interchangeable. This improved repairability, trade efficiency, and military organization. Copper-based bronze made early mass production possible long before modern industry.

This period also accelerated the history of copper wire, although in a primitive form. Thin copper strips and rods were used for binding, reinforcement, and decorative inlays. These early applications demonstrate an increasing awareness of copper’s flexibility and tensile behavior.

Economic and Social Implications

The Bronze Age elevated copper from a useful material to an economic driver. Copper sources became strategic assets. Control over mines and trade routes directly influenced political power. This relationship between material supply and authority is a recurring theme throughout the history of copper.

As demand increased, copper’s value became more sensitive to availability. Although formal pricing systems did not yet exist, scarcity and access clearly affected exchange rates. This period laid early foundations for what would later become the history of copper prices and the price history of copper.

Copper objects were no longer limited to elite or ritual use. They became integral to agriculture, construction, transportation, and warfare. This widespread adoption reinforced copper’s status as an essential material rather than a luxury.

Technological Maturity of Copper Metallurgy

By the height of the Bronze Age, copper metallurgy had reached a level of technical maturity. Smelting temperatures were better controlled. Alloy ratios were more consistent. Casting molds became more complex. These advancements reflect a deeper understanding of copper’s behavior under heat and stress.

From my viewpoint, this maturity marks a defining chapter in the history of copper element. Copper was no longer experimental. It was reliable. Its properties were predictable. This predictability allowed societies to plan production, manage resources, and scale infrastructure.

The Bronze Age demonstrates that copper’s value did not lie solely in innovation, but in stability. This stability explains why copper maintained relevance even as new materials emerged. Its adaptability ensured its continuous presence across successive technological phases.

When evaluated within the broader history of copper, the Bronze Age confirms one essential truth: copper was not merely part of progress—it enabled progress. Its role as the foundation of bronze ensured that copper remained indispensable in shaping early technological systems.

The Industrial Revolution and the Rise of Copper Production

In the history of copper, the Industrial Revolution marks a decisive structural shift. From my perspective, this period transformed copper from a historically important material into a core industrial commodity. Production methods, demand intensity, and application scope all changed fundamentally. Copper was no longer shaped mainly by craftsmanship or regional tradition. It became shaped by machines, systems, and industrial scale.

What distinguishes this stage in the history of copper is not discovery, but acceleration. Copper production expanded faster than at any previous point. This expansion was driven by mechanization, energy transition, and the need for reliable conductive and structural materials.

Mechanization and the Transformation of Copper Mining

Before the Industrial Revolution, copper extraction relied heavily on manual labor. During industrialization, mining entered a new phase. Steam engines enabled deeper shafts, improved drainage, and higher output. From a technical standpoint, this advancement redefined the history of copper mining.

Copper ore could now be extracted from previously inaccessible depths. Production volumes increased. Ore quality standards improved through mechanical sorting and early processing techniques. These developments reduced dependency on surface deposits and stabilized supply chains.

In the broader history of copper element, this period represents the transition from resource limitation to managed extraction. Copper availability became a function of technology rather than geography alone. This shift had lasting consequences for industrial planning and national development.

Smelting Efficiency and Production Scaling

Industrialization also reshaped copper smelting. Traditional furnaces were replaced or enhanced by coal-fired and later coke-based systems. Higher temperatures and better airflow control allowed for more efficient separation of copper from ore.

From my analysis, these improvements significantly reduced material loss and increased output consistency. This technical refinement strengthened copper’s reliability as an industrial input. The history of copper at this stage is defined by process optimization rather than experimentation.

Standardized ingots and refined copper grades began to appear. This standardization enabled predictable performance in manufacturing and infrastructure projects. It also laid the foundation for pricing mechanisms, contributing to the early formation of the history of copper prices.

Need Help? We’re Here for You!

Copper and the Rise of Industrial Infrastructure

One cannot examine the history of copper during the Industrial Revolution without addressing infrastructure. Copper became essential in machinery, piping systems, boilers, and industrial equipment. Its resistance to corrosion and ability to withstand repeated stress cycles made it ideal for factory environments.

Copper’s expanding role in industrial systems increased demand dramatically. Production was no longer reactive. It was anticipatory. Manufacturers required stable copper supply to maintain operational continuity. This dependency elevated copper to a strategic industrial material.

At this stage, the brief history of copper intersects directly with economic development. Regions with reliable copper access gained industrial advantages. Those without it faced constraints on growth.

Early Electrical Applications and Material Reliability

Although full electrification would emerge later, early electrical experimentation during the Industrial Revolution further reinforced copper’s importance. Copper’s conductivity had been observed empirically long before it was scientifically explained. As experimental electrical systems developed, copper naturally became the preferred material for conductors.

This period marks the early history of copper wire, where copper began transitioning from mechanical applications to energy transmission roles. Even in its initial forms, copper wiring demonstrated durability and efficiency unmatched by alternative materials available at the time.

From a materials perspective, this adaptability is central to understanding the history of copper element. Copper’s ability to serve mechanical, thermal, and conductive functions simultaneously made it irreplaceable in industrial environments.

Economic Impact and Market Expansion

As production increased and applications expanded, copper markets became more structured. Supply, demand, and transportation costs began to influence valuation. While modern commodity exchanges did not yet exist, pricing behavior became more systematic.

This phase contributed directly to the early price history of copper. Copper’s value increasingly reflected industrial demand rather than ornamental or symbolic worth. This shift reinforced copper’s identity as an economic indicator.

In my view, this economic transformation is a defining feature of the history of copper during industrialization. Copper evolved from a material used in industry to a material that shaped industry itself.

Copper as an Industrial Constant

By the end of the Industrial Revolution, copper had achieved a new status. It was no longer transitional. It was foundational. Production systems were built around its properties. Industrial designs assumed its availability.

This stage in the history of copper demonstrates a clear pattern: whenever production systems grow in complexity, copper’s relevance increases. Its consistency, scalability, and adaptability made it indispensable in an era defined by mechanization and expansion.

Modern Applications of Copper: Technology and Industry

In the history of copper, the modern era represents a phase of diversification rather than replacement. From my professional perspective, copper did not lose relevance with technological advancement. Instead, its role expanded into new domains as industrial systems became more complex, interconnected, and performance-driven.

What defines modern copper use is not novelty, but integration. Copper is embedded into almost every critical system that supports contemporary technology and industry. This reality reinforces copper’s long-term stability within the history of the element copper.

Copper as a Core Industrial Material

Modern industry relies on copper for its predictable physical and chemical properties. Copper offers an uncommon combination of electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, corrosion resistance, and mechanical workability. These characteristics explain why copper remains irreplaceable across multiple sectors.

In the history of copper, this stage shows continuity rather than disruption. While manufacturing technologies have evolved, copper’s fundamental behavior has remained consistent. Engineers and designers continue to specify copper because its performance is well understood and reliable.

Copper is widely used in industrial machinery, heat exchangers, piping systems, and precision components. Its ability to maintain integrity under thermal stress makes it especially valuable in high-load environments. These applications reflect the mature phase of the history of copper tooling, where copper components are engineered rather than handcrafted.

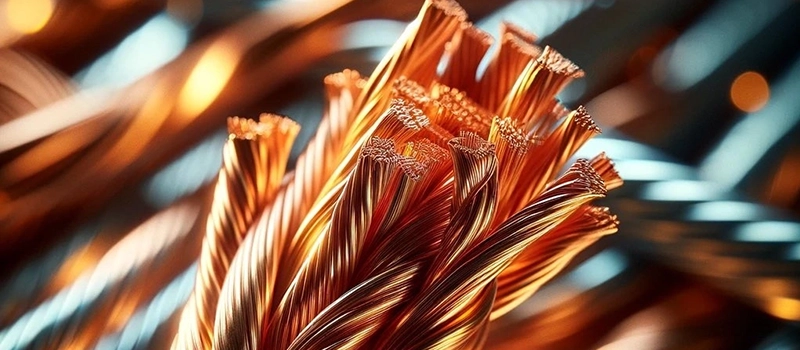

Electrical Systems and the Expansion of Copper Wire

No discussion of modern copper use is complete without addressing electrical systems. The expansion of power generation, transmission, and distribution significantly intensified copper demand. As a result, the history of copper wire became one of the most influential branches of the broader history of copper.

Copper’s superior conductivity minimizes energy loss. Its ductility allows for efficient wire drawing. Its resistance to fatigue ensures long service life. These factors explain why copper remains the preferred material for electrical wiring, motors, transformers, and grounding systems.

From my analysis, copper’s dominance in electrical applications is not simply historical inertia. It is the result of measurable performance advantages. Even with the introduction of alternative materials, copper continues to set the benchmark for efficiency and safety.

Copper in Manufacturing and Precision Engineering

Modern manufacturing places high demands on material consistency. Copper meets these demands through standardized grades and controlled production processes. Refined copper can be tailored to specific applications, supporting precision machining and forming.

This adaptability reflects a mature stage in the history of copper element. Copper is no longer valued only for what it is, but for how precisely it can be engineered. Sheet copper, copper alloys, and plated copper components are produced with tight tolerances to meet industrial specifications.

The history of copper plating is particularly relevant in modern manufacturing. Copper plating improves conductivity, corrosion resistance, and surface compatibility. It is widely applied in electronics, mechanical components, and industrial assemblies.

Copper in Thermal and Fluid Systems

Copper’s thermal conductivity has made it indispensable in heating and cooling systems. Heat exchangers, radiators, and HVAC components rely on copper to transfer energy efficiently. This application category further illustrates copper’s versatility within the history of copper.

In fluid systems, copper tubing is valued for its resistance to biofouling and corrosion. These properties support long-term reliability in industrial and commercial installations. From a lifecycle perspective, copper reduces maintenance requirements and system downtime.

These functional advantages reinforce copper’s position as a default engineering material rather than a specialized option.

Market Stability and Industrial Demand

Modern copper consumption is closely linked to industrial output. Manufacturing growth, infrastructure investment, and energy development directly influence demand. This relationship continues to shape the history of copper prices and the price history of copper.

From my viewpoint, copper’s modern applications demonstrate why it remains a strategic industrial resource. Its demand is diversified across sectors, reducing dependency on a single industry. This diversification contributes to copper’s long-term market resilience.

When viewed within the broader history of copper, modern applications confirm a consistent pattern. As technology advances, copper does not become obsolete. It becomes more deeply embedded.

The Impact of Copper on Trade and Economy

In the history of copper, few aspects are as influential as its role in shaping trade systems and economic structures. From my professional perspective, copper is not only a material commodity but also an economic signal. Wherever copper production, circulation, and consumption expanded, economic complexity followed.

Copper’s economic influence emerged early, but it became fully visible once production exceeded local consumption. At that point, copper transformed from a regional resource into a traded good. This transition marks a critical phase in the history of copper, where material utility intersected with market behavior.

Copper as a Trade Commodity

Throughout the history of copper, copper’s physical characteristics made it well suited for trade. It is durable, recyclable, divisible, and capable of retaining value over time. These traits allowed copper to circulate across long distances without significant degradation.

As production volumes increased, copper began to move systematically between regions. Mining centers supplied refining hubs. Refining hubs supplied manufacturing zones. This flow created early supply chains. In economic terms, copper became one of the first materials to support sustained interregional trade.

From my analysis, this trade-based circulation is fundamental to understanding the history of copper prices. Value was no longer determined solely by craftsmanship or symbolism. It was increasingly shaped by availability, transport cost, and demand concentration.

Regional Specialization and Economic Dependence

As copper trade expanded, regions began to specialize. Some areas focused on mining. Others on smelting, fabrication, or tool production. This specialization strengthened economic interdependence. In the history of copper, this marks the emergence of material-driven economic roles.

Copper-rich regions gained leverage. Control over copper resources influenced political power and trade negotiations. In contrast, copper-deficient regions developed commercial strategies to secure supply. This imbalance directly affected the price history of copper, as scarcity and access dictated exchange value.

Copper’s economic role also extended into taxation and state revenue. Governments recognized copper’s consistent demand and used it as a source of income through controlled production and trade regulation. This institutional involvement further embedded copper into economic systems.

Copper as an Indicator of Economic Activity

In my view, one of the most overlooked aspects of the history of copper is its function as an economic indicator. Copper consumption closely tracks levels of construction, manufacturing, and infrastructure development. When economic activity expands, copper demand rises. When it contracts, demand softens.

This pattern was observable long before modern economic theory. Historical records show that periods of expansion coincided with increased copper movement and higher relative value. Conversely, disruptions in production or trade often led to shortages and price volatility.

These dynamics contributed to the gradual formation of pricing mechanisms. Over time, copper’s value became less arbitrary and more responsive to market forces. This responsiveness is central to the long-term history of copper prices.

The Evolution of Copper Markets

As trade networks matured, copper markets became more organized. Standardized weights, grades, and forms improved transaction efficiency. This standardization reduced uncertainty and encouraged broader participation in copper trade.

From a structural standpoint, this evolution represents a key development in the history of copper element. Copper was no longer exchanged solely as finished goods. It was traded as raw material, semi-finished products, and standardized units. This flexibility expanded its economic reach.

Copper’s recyclability also played a role. Re-melting and reuse stabilized supply and moderated extreme scarcity. This circular behavior supported long-term market resilience, reinforcing copper’s position as a reliable economic asset.

Long-Term Economic Significance

When viewed across centuries, the history of copper reveals a consistent economic pattern. Copper adapts to changing systems without losing relevance. As economies grew more complex, copper’s role shifted from symbolic to functional, from local to global.

In my professional assessment, copper’s enduring economic importance lies in its dual nature. It is both an industrial input and a traded asset. This duality allows copper to respond dynamically to economic change while maintaining intrinsic utility.

The impact of copper on trade and economy is therefore not incidental. It is structural. Copper has repeatedly shaped how societies produce, exchange, and assign value. This influence remains one of the most stable elements within the entire history of copper.

The Future of Copper: Innovations and Sustainability

When I examine the history of copper, one pattern remains remarkably consistent: copper adapts. Across every technological shift, copper has adjusted its role without losing relevance. In the modern context, this adaptability is increasingly defined by innovation, efficiency, and sustainability.

The future of copper is not speculative. It is grounded in existing industrial trajectories. As systems become more energy-intensive, interconnected, and environmentally constrained, copper’s intrinsic properties continue to align with emerging requirements. This alignment ensures that copper remains central to the ongoing history of copper.

Technological Innovation and Material Optimization

In the current phase of the history of copper, innovation focuses less on discovery and more on optimization. Advanced refining techniques improve purity. Alloy engineering tailors performance for specific applications. Manufacturing processes reduce waste while increasing precision.

From a materials engineering perspective, copper benefits from decades of accumulated knowledge. Its behavior under thermal, mechanical, and electrical stress is well documented. This predictability supports innovation rather than limiting it. Engineers can design systems around copper with high confidence in performance outcomes.

This optimization-driven approach represents a mature stage in the history of the element copper. Copper is no longer improved through trial alone, but through controlled experimentation and data-driven design.

Copper and Energy Efficiency

Energy systems are among the most copper-intensive sectors. Power generation, transmission, and distribution all rely heavily on copper components. As energy efficiency becomes a global priority, copper’s conductivity and durability gain additional importance.

In the history of copper, energy transitions have repeatedly increased demand. This pattern continues today. Copper minimizes energy loss, supports compact system design, and withstands long-term operational stress. These qualities make copper essential for modern energy infrastructure.

From my analysis, copper’s role in energy efficiency is not optional. It is structural. As efficiency standards tighten, copper usage becomes more precise rather than reduced. This trend reinforces copper’s long-term position within the history of copper prices.

Sustainability and the Circular Economy

Sustainability has become a defining theme in the modern history of copper. Copper’s recyclability distinguishes it from many alternative materials. It can be reused repeatedly without loss of performance, supporting circular production models.

This recyclability reduces dependency on primary mining and lowers environmental impact. From an economic standpoint, recycled copper stabilizes supply and moderates price volatility. These factors contribute to a more resilient price history of copper over time.

In my professional view, copper’s compatibility with sustainability goals is not incidental. It is a result of its fundamental physical stability. As industries adopt lifecycle-based planning, copper’s long service life and recyclability align directly with sustainability metrics.

Regulatory Pressure and Responsible Production

Another defining factor in the future history of copper is regulation. Environmental standards, labor requirements, and traceability expectations increasingly influence copper production and trade. These pressures reshape how copper is mined, refined, and distributed.

Rather than reducing copper’s relevance, regulation increases the value of efficiency and quality. Producers are incentivized to reduce waste, improve yield, and adopt cleaner technologies. This shift accelerates modernization across the copper supply chain.

From a historical perspective, regulation represents another evolutionary phase. The history of copper mining has always responded to external constraints—geological, technological, or social. Environmental responsibility is the latest constraint shaping copper’s future.

Long-Term Strategic Importance

When viewed within the full history of copper, the future appears less uncertain than many assume. Copper’s role continues to expand where reliability, efficiency, and sustainability intersect. Few materials meet these requirements simultaneously.

Copper’s strategic importance is reinforced by its broad application base. No single sector defines its demand. This diversification reduces systemic risk and supports long-term stability. As a result, copper remains both an industrial necessity and an economic constant.

In my assessment, the future chapter of the history of copper will not be defined by replacement, but by refinement. Copper will continue to evolve—not by changing what it is, but by improving how it is produced, applied, and reused.

Conclusion: The Timeless Value of Copper

The history of copper reveals a material that has continuously adapted to human needs without losing relevance. From early discovery to modern industry, copper’s durability, versatility, and economic significance have made it a constant foundation of technological progress and global development.