“The annealing process is one of the most widely used heat treatments in metallurgy, recommended by standards such as ASTM A1030 and DIN EN ISO 15787.”

—— Metallurgical Engineering Handbook

What Is the Annealing Process in Metalworking?

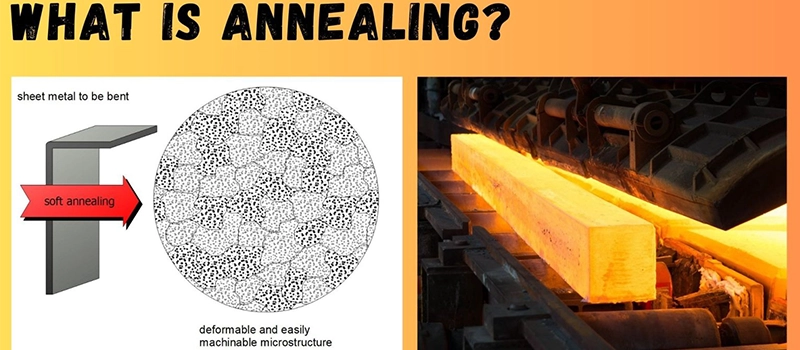

In metalworking, the annealing process refers to a controlled heat treatment applied to metals to modify their internal structure and mechanical behavior. Its primary purpose is to return the material to a more stable, workable, and predictable condition after it has been affected by manufacturing stress.

During metal processing such as casting, forming, rolling, or machining, metals are subjected to thermal and mechanical forces that alter their internal crystal arrangement. These changes often increase hardness and strength, but at the cost of ductility and flexibility. Annealing addresses this imbalance by intentionally altering the metal’s microstructure in a controlled manner.

From a metallurgical perspective, annealing is defined as a process that reduces internal stress, lowers hardness, and improves ductility without changing the metal’s chemical composition. It is not meant to strengthen metal through hardening, but rather to stabilize and condition it so that it behaves consistently during further manufacturing or in service.

In practical terms, annealed metal is easier to cut, bend, form, and weld. This is why annealing is widely used across steel, stainless steel, copper, aluminum, and other engineering metals. The process is considered a foundational treatment in metalworking because it prepares materials for subsequent operations while minimizing the risk of cracking, distortion, or unpredictable performance.

Simply put, annealing is the metallurgical method of restoring balance to a metal after stress, ensuring it remains functional, reliable, and suitable for industrial use.

Step-by-Step: The Full Annealing Process of Metal

The annealing process in metalworking follows a clearly defined thermal sequence designed to produce predictable and stable material properties. Although parameters vary by material type, the fundamental structure of the annealing process remains consistent across most metals used in industrial manufacturing.

This process is not arbitrary. Each step serves a distinct metallurgical purpose, and skipping or mismanaging any stage can lead to incomplete stress relief, uneven grain structure, or surface defects.

Step 1: Controlled Heating of the Metal

The annealing process begins with gradual and uniform heating of the metal to a predetermined temperature. This temperature is carefully selected based on the metal’s composition, prior processing history, and the desired outcome of the annealing process.

Heating must be controlled to prevent thermal shock or uneven temperature distribution. If the metal is heated too quickly, internal temperature gradients can form, leading to distortion or cracking. For this reason, industrial annealing furnaces are designed to raise temperature steadily and evenly across the entire workpiece.

At this stage, the goal of the annealing process is to bring the metal into a thermal condition where atomic mobility increases, allowing internal structural changes to occur without reaching the melting point.

Step 2: Temperature Holding (Soaking Phase)

Once the target temperature is reached, the metal enters the soaking phase of the annealing process. During this period, the metal is held at a stable temperature for a specific length of time.

This holding time is critical. It allows the entire cross-section of the metal part to reach thermal equilibrium. More importantly, it provides sufficient time for metallurgical transformations such as recrystallization and stress relaxation to take place.

The duration of this phase depends on factors such as:

- Material thickness

- Alloy composition

- Degree of prior cold work

Inadequate soaking can result in incomplete annealing, while excessive soaking may cause grain coarsening, which negatively affects mechanical properties.

Step 3: Controlled Cooling

The final stage of the annealing process is controlled cooling. Unlike hardening treatments that require rapid cooling, annealing typically relies on slow, regulated cooling to maintain structural stability.

Cooling is often carried out inside the furnace itself, allowing the temperature to decrease gradually. This slow cooling prevents the formation of new internal stresses and supports the development of a uniform grain structure.

The cooling rate directly influences the final hardness, ductility, and dimensional stability of the metal. An improperly controlled cooling phase can undermine the benefits achieved during heating and soaking, making this step just as critical as the earlier stages of the annealing process.

Why Process Control Matters in the Annealing Process

The effectiveness of the annealing process depends on precision at every step. Temperature accuracy, timing, and cooling control must be matched to the specific metal and application requirements.

In industrial environments, the annealing process is closely monitored using thermocouples, programmable controllers, and atmosphere regulation to ensure repeatability and quality consistency. This level of control is what allows annealing to deliver reliable results across high-volume production and critical components.

Types of Annealing Processes and Their Applications

The annealing process is not a one-size-fits-all treatment. In industrial metallurgy, it has evolved into several specific subtypes, each tailored to address different materials, processing histories, and end-use requirements. Understanding these variations is essential for selecting the right method to achieve targeted mechanical and structural properties.

Below are the most common types of annealing processes, along with their technical definitions and practical applications in metalworking.

1. Full Annealing

Full annealing is the most comprehensive form of the annealing process. It involves heating ferrous metals, typically carbon steel, to about 30–50°C above their upper critical temperature (Ac3), holding them long enough to allow complete phase transformation, and then slowly cooling—usually inside the furnace.

This process results in a coarse but uniform grain structure, reduces hardness, and restores ductility. Full annealing is commonly used:

- After casting or forging large steel parts

- To prepare components for further machining

- For structural steel requiring consistent performance

It is especially suitable when the metal will undergo further plastic deformation, such as deep drawing or rolling.

2. Process Annealing (Subcritical Annealing)

Process annealing is a low-temperature variant of the annealing process, where the metal is heated below the lower critical temperature (typically between 500–650°C). This prevents phase transformation but allows recovery and stress relief.

Unlike full annealing, process annealing is faster and less energy-intensive. It’s widely applied in:

- Low carbon steels after cold rolling

- Intermediate softening between forming operations

- Parts that don’t require a fully recrystallized structure

The goal is to restore ductility without drastically changing the microstructure, making it ideal for staged manufacturing processes.

3. Stress Relief Annealing

This annealing process targets internal residual stresses that accumulate during welding, machining, or cold forming. The metal is heated to a moderate temperature (typically 450–650°C), held briefly, and then cooled slowly.

Unlike full or process annealing, this type does not alter the metal’s microstructure or mechanical strength significantly. Instead, it prevents:

- Warping

- Dimensional instability

- Premature failure in service

It is often used in:

- Welded pressure vessels

- Precision-machined parts

- Large steel plates or frames

Stress relief annealing is essential when dimensional accuracy and mechanical reliability are non-negotiable.

4. Solution Annealing (Solution Heat Treatment)

Solution annealing is commonly applied to stainless steel and high-alloy materials. In this annealing process, the material is heated to high temperatures (usually between 1000–1100°C), dissolving secondary phases into a single-phase austenitic solution, then rapidly cooled—usually via water quenching.

Key outcomes:

- Dissolves carbides and other precipitates

- Maximizes corrosion resistance

- Restores weldability

Industries using solution annealing include:

- Medical device manufacturing (surgical stainless)

- Food-grade piping systems

- Aerospace and marine components

This process is vital for maintaining the corrosion-resistant properties of stainless steel.

Need Help? We’re Here for You!

5. Induction Annealing

Induction annealing is a localized and highly efficient non-contact annealing process using high-frequency electromagnetic fields to heat the metal. The annealing occurs very rapidly and is ideal for:

- Wire and tube production

- Automotive axle shafts

- Surface hardening or softening zones

This annealing process is advantageous when:

- Precision and speed are required

- Only a specific area of the workpiece needs treatment

- Production must be continuous or automated

It reduces energy loss and increases throughput, making it highly suitable for high-volume manufacturing lines.

6. Laser Annealing

Laser annealing is a modern annealing process that uses a focused laser beam to selectively heat thin metal layers. It’s especially effective in:

- Semiconductor fabrication (annealing doped silicon layers)

- Surface treatments of micro components

- Thin metal film recrystallization

Benefits include:

- Ultra-fast heating and cooling cycles

- Minimal thermal distortion

- Precision targeting of annealed zones

Though not widely used in traditional metalworking yet, laser annealing is growing in importance for high-tech, miniature, or energy-sensitive applications.

Benefits of Annealing in Material Properties

The annealing process is not just a technical step in manufacturing—it’s a strategic tool for enhancing the material properties of metals at the microscopic and macroscopic levels. By carefully applying thermal energy under controlled conditions, the annealing process permanently alters the internal structure of metal, leading to measurable improvements in performance, workability, and stability.

1. Improved Ductility

Ductility is the ability of a metal to deform under tensile stress without fracturing. When a metal undergoes cold working—such as stamping, drawing, or rolling—it becomes harder but also more brittle.

The annealing process reverses work hardening by enabling the formation of new, strain-free grains through recrystallization. This restores the metal’s ability to bend or stretch without cracking, which is essential for applications requiring forming or welding.

Industries such as automotive and HVAC rely on annealed metal sheets and tubing specifically for this reason.

2. Reduced Hardness

While hardness is desirable in some cases, excessive hardness can make a metal difficult to machine or prone to cracking under stress. The annealing process lowers the hardness of metal by reducing dislocation density within its crystal lattice.

This softening effect makes the metal easier to cut, drill, and form. It also extends tool life during machining and reduces the risk of surface defects.

Softened metals are especially important for precision components, where ease of machining is critical to dimensional control.

3. Enhanced Machinability

Machinability refers to how easily a material can be cut or shaped using tools. The annealing process improves machinability by creating a uniform and relaxed grain structure, minimizing tool vibration and resistance.

For example, annealed steel generates less tool wear and allows for higher feed rates in CNC machining. This leads to shorter production cycles and lower manufacturing costs.

In high-volume production environments, the increase in machinability from annealing directly contributes to throughput and consistency.

4. Relief of Internal Stresses

Internal stresses are often invisible but can cause warping, cracking, or failure during subsequent processing or use. These stresses are introduced during welding, forming, or rapid cooling.

The annealing process neutralizes these internal stresses by allowing atomic rearrangement and thermal equalization. This prevents dimensional instability and increases long-term reliability.

This benefit is especially crucial for structural components, pressure vessels, and precision assemblies where tolerance and integrity are non-negotiable.

5. Refined Grain Structure

The microstructure of a metal—specifically its grain size and shape—directly affects strength, toughness, and fatigue resistance. Cold work distorts the grains, making them elongated and irregular.

Annealing facilitates grain refinement by allowing the metal to recrystallize and form uniform, equiaxed grains. This improves not only the appearance of the metal but also its fatigue performance and resistance to crack propagation.

In aerospace, medical, and energy sectors, materials with refined grain structures are often mandated by quality standards.

6. Improved Magnetic and Electrical Properties

For certain metals, especially soft magnetic materials like silicon steel or pure iron, the annealing process significantly enhances magnetic permeability and electrical conductivity.

By reducing dislocations and impurities that impede electron or domain movement, annealing improves signal flow and reduces energy losses. This makes it indispensable in the production of:

- Transformers

- Electric motors

- Electronic shielding

7. Restoration of Corrosion Resistance

In stainless steels, the annealing process (especially solution annealing) helps restore corrosion resistance by dissolving chromium carbides and homogenizing alloying elements.

This is essential for parts exposed to corrosive environments such as:

- Food processing equipment

- Marine components

- Chemical pipelines

Without proper annealing, the protective chromium oxide layer may not fully reform, leading to localized corrosion such as pitting or intergranular attack.

Factors Influencing the Annealing Process

The annealing process must be carefully controlled to achieve consistent and desirable results. Variations in temperature, time, atmosphere, material type, and even cooling rate can drastically affect the outcome. Understanding these influencing factors is crucial for ensuring that the annealing process delivers optimal improvements in mechanical and structural properties.

1. Annealing Temperature

Temperature is the single most important variable in the annealing process. Each metal or alloy has a specific temperature range—usually just below its melting point—where atomic movement becomes active enough for stress relief, recrystallization, or phase transformation.

If the annealing temperature is too low, the process will be incomplete, and internal stresses or strain-hardened structures may persist. If the temperature is too high, it can lead to:

- Grain coarsening

- Surface oxidation or scaling

- Reduced mechanical strength

Precision in temperature selection ensures that the metal reaches the correct structural phase without damage.

2. Holding (Soaking) Time

Once the desired temperature is reached, the material must be held at that temperature long enough to allow full structural transformation. This is referred to as the soaking time.

Factors influencing soaking time include:

- Metal thickness

- Part geometry

- Initial internal stress level

- Desired metallurgical outcome

Insufficient soaking results in non-uniform properties across the workpiece, while excessive soaking may cause unwanted grain growth or surface reactions.

In industrial practice, holding time is typically calculated as a function of part thickness (e.g., minutes per millimeter).

3. Cooling Rate

The rate at which the metal is cooled after soaking directly affects the final grain structure and residual stress level. In the annealing process, cooling is usually done slowly to allow atoms to settle into a relaxed and uniform arrangement.

Cooling methods include:

- Furnace cooling (most common and controlled)

- Air cooling (faster, less uniform)

- Gas or inert cooling (used to avoid oxidation)

- Water quenching (rare in annealing, used in solution annealing)

Improper cooling—either too fast or too uneven—can reintroduce stress, cause warping, or even reverse some of the benefits achieved during heating.

4. Type and Composition of the Metal

Different metals and alloys respond to the annealing process in different ways. For example:

- Low-carbon steel softens readily and requires lower temperatures.

- High-carbon steel is more sensitive to grain growth and must be annealed carefully.

- Stainless steel demands high-temperature solution annealing followed by rapid cooling to restore corrosion resistance.

- Aluminum and copper alloys require lower temperatures and shorter soak times to prevent over-aging or melting.

Selecting the appropriate annealing parameters depends heavily on chemical composition, alloying elements, and prior mechanical history.

5. Furnace Atmosphere

The environment inside the furnace can significantly influence the surface quality and metallurgical outcome of the annealing process. Furnace atmospheres are typically classified as:

- Oxidizing (air) – simple but may cause scale or discoloration

- Reducing (hydrogen or endothermic gas) – prevents oxidation and cleans surfaces

- Inert (nitrogen or argon) – used for high-purity or reactive metals

Choosing the right atmosphere is critical for surface finish and preventing unwanted chemical reactions during annealing.

6. Initial Condition of the Workpiece

The starting state of the metal—whether it has been cold-worked, welded, forged, or previously heat treated—affects how it will respond to annealing.

For example:

- Cold-worked materials require higher annealing temperatures to initiate recrystallization.

- Welded components may contain stress concentrations that need targeted stress relief annealing.

- Pre-hardened metals might need soft annealing to enable further machining.

Accurate knowledge of the metal’s prior processing history ensures the annealing process is applied correctly.

7. Equipment and Process Control

Modern annealing processes depend on precise control systems to maintain temperature stability, soaking time, and cooling profiles. Inaccurate sensors, furnace hot spots, or inconsistent batch loading can lead to:

- Uneven heating

- Part-to-part variation

- Incomplete annealing

Industries with strict quality requirements often employ programmable logic controllers (PLCs), thermal cameras, and digital process monitoring to ensure repeatability in the annealing process.

Annealing vs. Other Heat Treatment Processes

In industrial metal treatment, the annealing process is one of several thermal methods used to alter the properties of metals. While annealing focuses on softening and stress relief, other processes like normalizing, tempering, and quenching serve different purposes.

Below is a comparison of the most common heat treatment methods in metalworking:

🔍 Comparative Table: Heat Treatment Processes

| Process | Purpose | Temperature Range (°C) | Cooling Method | Resulting Properties | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annealing | Soften metal, relieve stress, improve ductility | 400–1100°C (varies by metal) | Slow cooling (often in furnace) | Soft, ductile, stress-free | Pre-machining, forming, welding prep |

| Normalizing | Refine grain structure, increase uniformity | 750–950°C | Air cooling | Stronger than annealed, less ductile | Structural components, forged parts |

| Tempering | Reduce brittleness after hardening | 150–650°C | Air cooling | Balanced hardness and toughness | Tools, gears, hardened steel parts |

| Quenching | Harden the metal rapidly | 800–950°C | Rapid cooling (oil, water, or air) | Very hard, brittle if untempered | Blades, wear parts, high-strength tools |

| Solution Annealing | Dissolve carbides in alloys (esp. stainless steel) | 1000–1150°C | Rapid cooling (often water quench) | Restores corrosion resistance, homogeneity | Stainless steel tubing, medical parts |

| Stress Relief Annealing | Eliminate residual stresses without phase change | 450–650°C | Slow cooling | Maintains hardness, reduces distortion | Weldments, precision machined parts |

Conclusion

The annealing process is essential in modern metalworking. By relieving stress, improving ductility, and refining structure, it ensures metals are reliable, machinable, and ready for demanding industrial applications. Mastering this process means mastering material performance.