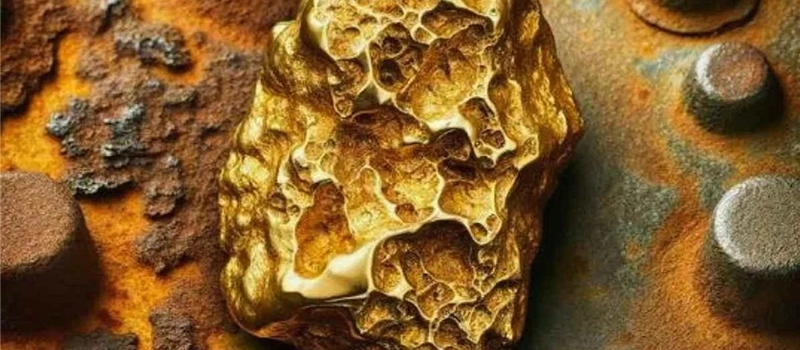

Gold corrosion resistance explains why gold remains unchanged while other metals degrade under the same environmental conditions. Why does this property allow gold to outperform steels and copper alloys in certain industrial uses? Why does gold plating succeed in some applications but fail prematurely in others? These questions arise when gold is selected without fully understanding how its corrosion behavior works in real systems.

According to corrosion engineering references such as the ASM Handbook and ISO materials guidance, gold is classified as a noble metal with extremely low chemical reactivity. Its stability is inherent to its atomic structure rather than the result of surface films or treatments. However, this stability changes when gold is alloyed, applied as a thin layer, or paired with dissimilar metals.

In industrial applications, performance depends on context rather than reputation. Purity level, plating thickness, mechanical wear, and environmental exposure all determine whether long-term stability is achieved. Understanding these factors is essential to avoid overestimating capability or misapplying gold where other materials may be more appropriate.

What Gold Corrosion Resistance Means in Industrial Contexts

Definition of Corrosion Resistance in Engineering

Gold corrosion resistance in engineering refers to the ability of gold to maintain surface chemistry and functional stability when exposed to environments that cause oxidation or degradation in most other metals. In industrial applications, this definition emphasizes performance reliability rather than material loss.

Gold corrosion resistance is evaluated by whether electrical conductivity, contact behavior, or precision surface interaction remains unchanged over time. This focus distinguishes gold from structural materials where corrosion is measured primarily by mass loss or strength reduction.

Why Gold Is Classified as a Noble Metal

Gold corrosion resistance originates from gold’s classification as a noble metal with extremely low chemical reactivity. Under normal industrial conditions, gold does not react with oxygen, moisture, or most acids and bases encountered during manufacturing or service.

Because gold corrosion resistance is intrinsic rather than dependent on a passive oxide layer, surface properties remain stable. This characteristic is critical in applications where even thin reaction films would interfere with electrical or mechanical function.

Difference Between Rust, Corrosion, and Tarnish

Gold corrosion resistance must be understood in contrast to rust and tarnish. Rust is a specific corrosion mechanism limited to iron-based materials and does not apply to gold. Corrosion is a broader term describing chemical or electrochemical degradation of metals.

Gold corrosion resistance prevents both rust and tarnish under normal conditions. When surface degradation is observed in gold-containing systems, it is typically caused by alloying elements, substrate exposure, or galvanic interaction rather than gold itself.

Fundamental Reasons Gold Resists Corrosion

Atomic Structure and Chemical Inertness

Gold’s resistance to chemical attack originates at the atomic level. Its electron configuration makes it energetically unfavorable for gold atoms to participate in oxidation or reduction reactions under normal industrial conditions. Unlike reactive metals, gold does not readily lose electrons to form stable oxides or compounds.

From an engineering standpoint, this inertness means the surface chemistry of gold remains stable over long periods. There is no progressive surface change that would alter electrical conductivity, contact resistance, or precision fit, even in environments where other metals degrade.

Interaction with Oxygen, Moisture, and Common Chemicals

In air and moisture, gold remains unchanged. It does not form an oxide layer, hydroxide, or sulfide film during normal exposure. This behavior distinguishes gold from metals that rely on passive films for protection, which can break down or thicken over time.

Most common industrial chemicals, including weak acids and bases, do not react with gold. Only highly aggressive agents or specific chemical combinations can attack it. As a result, gold maintains surface stability in environments where corrosion control is otherwise difficult.

Environmental Conditions Where Gold Remains Stable

Gold remains stable across a wide range of temperatures and atmospheric conditions encountered in industrial service. Humidity, temperature cycling, and storage time have minimal effect on its surface condition when mechanical damage is absent.

However, stability should not be confused with indestructibility. Mechanical wear, abrasion, or exposure of underlying substrates can compromise performance. In practical applications, maintaining surface integrity is as important as the metal’s inherent chemical resistance.

Corrosion Resistance of Pure Gold vs Gold Alloys

Purity Levels and Their Effect on Stability

Gold corrosion resistance is highest in pure gold because the metal’s chemical inertness is not diluted by reactive alloying elements. In industrial terms, high-purity gold maintains surface stability even after long-term exposure to air, moisture, and most non-aggressive chemicals.

As purity decreases, gold corrosion resistance becomes increasingly dependent on the behavior of added elements. While the gold matrix itself remains stable, alloying metals introduce sites that can oxidize or react, altering surface chemistry and long-term performance.

Role of Alloying Elements in Reducing Corrosion Resistance

Alloying elements such as copper, silver, or nickel are added to gold to improve strength, hardness, or wear resistance. However, these elements do not share the same corrosion resistance as gold. As a result, gold corrosion resistance in alloys is no longer an intrinsic property of the entire material.

In industrial environments, corrosion often initiates at alloy-rich regions or grain boundaries. This localized degradation does not mean gold itself is corroding, but it does reduce the functional benefit associated with gold corrosion resistance, especially in precision or electrical applications.

Why Lower-Purity Gold Can Tarnish in Service

Lower-purity gold alloys may tarnish or discolor over time because alloying elements react with sulfur compounds, moisture, or industrial contaminants. This surface change is frequently misinterpreted as a failure of gold corrosion resistance, when it is actually the reaction of non-gold constituents.

In practical applications, this distinction matters. Selecting lower-purity gold for cost or strength reasons reduces effective gold corrosion resistance and may compromise long-term surface stability. Engineers must balance mechanical requirements against the corrosion performance that pure gold provides.

Gold Corrosion Resistance in Plated and Coated Systems

Gold Plating Thickness and Performance

Gold corrosion resistance in plated systems depends strongly on coating thickness. Thin decorative or flash gold layers provide initial surface stability but offer limited long-term protection in industrial environments. As thickness decreases, the probability that defects expose the underlying substrate increases, reducing effective gold corrosion resistance.

In functional applications such as electrical contacts, sufficient plating thickness is required to ensure that the gold layer remains continuous over time. Mechanical wear, vibration, or repeated contact cycles can quickly breach thin coatings, allowing corrosion processes to initiate beneath the gold surface.

Porosity, Pinholes, and Substrate Interaction

Porosity is one of the primary factors limiting gold corrosion resistance in plated components. Microscopic pinholes formed during deposition allow moisture, oxygen, or contaminants to reach the base material. While the gold itself remains chemically stable, corrosion of the substrate undermines overall system performance.

When gold corrosion resistance is specified for plated parts, substrate compatibility becomes critical. Reactive base metals accelerate galvanic effects once exposed, leading to rapid degradation that appears as plating failure even though the gold layer itself is not reacting.

Typical Failure Modes of Gold-Plated Components

Most failures attributed to reduced gold corrosion resistance are mechanical or structural rather than chemical. Wear-through, abrasion, and deformation disrupt the integrity of the gold layer, exposing less corrosion-resistant materials underneath.

In industrial use, gold corrosion resistance should be evaluated as a system property rather than a material property alone. Plating quality, thickness control, substrate selection, and service conditions collectively determine whether long-term performance expectations are met.

Industrial Applications That Rely on Gold Corrosion Resistance

Electrical Contacts and Connectors

Gold corrosion resistance is a critical requirement in electrical contacts and connectors where stable conductivity must be maintained over long service periods. In these applications, even thin oxide or sulfide films would increase contact resistance and cause signal instability. Because gold does not form such films under normal conditions, contact performance remains consistent.

In industrial environments with humidity, airborne contaminants, or temperature cycling, gold corrosion resistance ensures that mating surfaces remain clean without the need for frequent maintenance. This is especially important in low-voltage or low-contact-force systems where surface condition directly affects functionality.

Electronics and Signal Transmission Components

In electronic assemblies, gold corrosion resistance supports reliable signal transmission by preserving surface integrity at interfaces such as edge connectors, bonding pads, and switching contacts. Corrosion at these locations would introduce noise, intermittent connections, or complete signal loss.

Gold is often used selectively rather than extensively in these systems. Its corrosion resistance is applied where failure risk is highest, allowing designers to balance performance and cost. In this context, long-term stability is valued more than bulk material strength.

Precision Components and Low-Wear Environments

Gold corrosion resistance is also applied in precision components where dimensional stability and surface consistency are critical. Examples include relay contacts, sensor interfaces, and specialized mechanical elements operating under light loads.

In these applications, corrosion is not expected to cause structural damage but can disrupt function through surface change. Gold corrosion resistance prevents this mode of failure, provided mechanical wear and abrasion are limited. Where wear dominates, gold alone may not be sufficient, and system design must account for both chemical and mechanical factors.

Practical Limits of Gold Corrosion Resistance

Chemical Environments That Can Affect Gold

Gold corrosion resistance is extremely high in most industrial environments, but it is not absolute. Certain chemical combinations can attack gold under specific conditions. Strong oxidizing agents, halogens, and mixtures such as aqua regia can dissolve gold by disrupting its chemical stability.

In industrial practice, these environments are uncommon, but they do exist in chemical processing, laboratory handling, and specialized manufacturing steps. When gold corrosion resistance is relied upon, exposure to aggressive chemicals must be evaluated carefully rather than assumed safe by default.

Galvanic Effects When Gold Is Paired with Other Metals

Gold corrosion resistance can be compromised indirectly through galvanic interactions. When gold is electrically connected to less noble metals in the presence of an electrolyte, the base metal corrodes preferentially. While the gold surface remains intact, degradation of the adjacent material undermines system reliability.

This effect is especially relevant in plated systems and mixed-metal assemblies. Improper pairing can create corrosion pathways that appear as gold failure but are actually driven by galvanic imbalance. Managing material combinations is therefore essential when specifying gold corrosion resistance.

Wear, Abrasion, and Mechanical Damage

Gold corrosion resistance does not protect against mechanical damage. Wear, abrasion, and repeated contact can remove or thin gold layers, exposing underlying materials that lack corrosion resistance. Once this occurs, chemical degradation progresses rapidly, even though the gold itself remains inert.

In industrial applications, corrosion resistance and wear resistance must be considered together. Gold performs well where chemical stability is critical and mechanical stress is low. Where abrasion dominates, gold corrosion resistance alone is insufficient without supporting design measures.

Gold Compared with Other Corrosion-Resistant Metals

Gold vs Stainless Steel

Gold corrosion resistance differs fundamentally from that of stainless steel. Stainless steels rely on a chromium-rich passive oxide layer to slow corrosion. This layer can break down under chlorides, low oxygen conditions, or mechanical damage, leading to localized attack.

Gold corrosion resistance does not depend on passivation. The surface remains chemically stable without forming films that can degrade or detach. In applications where surface chemistry directly affects function, such as electrical contacts, gold provides more reliable long-term behavior than stainless steel, despite lower mechanical strength.

Gold vs Nickel and Chromium Plating

Nickel and chromium plating are commonly used to improve corrosion resistance and wear performance at lower cost. These coatings provide barrier protection but are susceptible to cracking, porosity, and breakdown over time. Once defects form, corrosion progresses rapidly at exposed areas.

Gold corrosion resistance in plated systems behaves differently. Even when thin, gold does not chemically degrade, so failure typically results from mechanical wear or substrate exposure rather than coating breakdown. This makes gold preferable in low-wear, high-reliability environments where surface stability is critical.

When Gold Is Technically Necessary

Gold corrosion resistance becomes technically necessary when even minor surface reactions cause unacceptable performance loss. Examples include low-voltage electrical contacts, signal transmission interfaces, and precision components operating with minimal contact force.

In these cases, alternative materials may appear adequate during initial testing but degrade over time due to surface oxidation or contamination. Gold is selected not for structural durability, but to eliminate corrosion-related variability that cannot be controlled through design or maintenance alone.

Conclusion

Gold corrosion resistance provides exceptional surface stability in industrial applications where even minor chemical change can cause functional failure. Its effectiveness depends on purity, application method, and operating conditions rather than reputation alone. When used where chemical stability matters more than wear or structural strength, gold delivers reliable long-term performance.