Do your steel parts crack or break during hot working or casting? Are you noticing brittleness in components that should withstand high temperatures? Is it possible your materials are suffering from an invisible defect that escapes early detection?

Hot shortness could be the hidden problem undermining your steel quality. This high-temperature brittleness is often caused by sulfur or copper impurities that segregate along grain boundaries, making steel crack when exposed to elevated processing temperatures. As noted in European compliance commentary:

“Hot shortness poses a significant risk to the structural integrity of steel products intended for critical applications, especially when impurity levels exceed controlled thresholds.” (source)

Steel that looks perfect after casting can still fail when forged, welded, or heat-treated. If you’re not actively managing hot shortness, you could be setting your production up for hidden failures.

What Is Hot Shortness in Steel Alloys?

Definition and Temperature Range

Hot shortness is a metallurgical defect in steel alloys characterized by a loss of ductility at elevated temperatures, typically between 800°C and 1200°C. It occurs during high-temperature processes such as rolling, forging, or welding, where thermal exposure coincides with mechanical deformation. This leads to intergranular cracking, often invisible during initial inspection but critical in later processing stages.

Mechanism of Brittleness at Grain Boundaries

The defect originates from the segregation of impurities—mainly sulfur and copper—at grain boundaries. In steels where sulfur is not properly controlled, iron sulfide (FeS) can form. FeS melts at a lower temperature than steel, and during reheating, it forms a thin liquid film along grain boundaries. This weakens the steel’s internal structure and promotes crack initiation when mechanical force is applied.

Role of Copper Segregation

Copper contamination, often present in recycled steels, can also contribute to hot shortness. Upon heating, copper tends to segregate at grain boundaries, forming brittle films or oxides that behave similarly to FeS. These segregated zones reduce grain cohesion and act as stress concentrators under load, leading to premature failure during thermal processing.

Susceptible Steel Grades and Industrial Implications

Low-carbon and low-alloy steels are most prone to hot shortness. These grades are widely used across industries, making proper chemical control essential. Manganese is typically added to bind with sulfur and form manganese sulfide (MnS), which has a higher melting point and does not embrittle grain boundaries. When the manganese-to-sulfur ratio is insufficient, FeS formation—and therefore hot shortness—is more likely.

Regulatory Expectations and Quality Requirements

Because hot shortness compromises structural integrity, it is a concern in industries requiring high-reliability components, such as automotive, petrochemical, construction, and mining. CE certification and related quality standards require manufacturers to maintain documentation and controls on steel composition and thermal behavior. These controls are essential to prevent material failures caused by high-temperature brittleness.

Root Causes of Hot Shortness in Steel

Sulfur as a Primary Cause

One of the most common causes of hot shortness in steel alloys is sulfur. During the steelmaking process, sulfur may not be completely removed and can remain as a residual impurity. When sulfur levels are too high and not properly balanced by manganese, it reacts with iron to form iron sulfide (FeS). The melting point of FeS is significantly lower than that of steel, which allows it to partially liquefy at typical forging or rolling temperatures. This liquid phase at grain boundaries weakens the steel structure and promotes intergranular cracking.

Manganese-to-Sulfur Ratio

The addition of manganese is the standard method used to counter the effects of sulfur in steel. Manganese preferentially combines with sulfur to form manganese sulfide (MnS), which has a higher melting point and a more benign distribution in the microstructure. When the manganese-to-sulfur ratio falls below the required level, FeS is more likely to form instead of MnS. This imbalance increases the risk of hot shortness during high-temperature processing. Controlling this ratio is therefore a key preventive measure in steel alloy formulation.

Copper Segregation in Recycled Steels

Copper is another element that contributes to hot shortness, especially in recycled or scrap-based steel production. Copper does not volatilize during steelmaking and tends to concentrate at grain boundaries. During heating, these copper-enriched zones can oxidize or melt, forming brittle films that promote crack initiation. The effect is more pronounced when steel is processed in oxidizing atmospheres or at temperatures above 1000°C. Copper-induced hot shortness is often more difficult to detect in its early stages but can cause significant issues during forming operations.

Additional Residual Elements

Other residual elements, such as tin, antimony, and arsenic, may also contribute to grain boundary weakening in certain steel grades. Although their influence is typically less severe than that of sulfur or copper, the combined presence of multiple trace elements can lead to cumulative embrittlement effects. These elements are more difficult to control in scrap-based production routes and require careful monitoring and refining strategies to minimize their impact.

Influence of Steelmaking Methods

The specific steelmaking method used can also affect the likelihood of hot shortness. In electric arc furnace (EAF) steelmaking, where recycled materials are heavily used, there is a higher risk of residual element buildup, especially copper. In contrast, basic oxygen furnace (BOF) processes typically offer more control over raw material composition and impurity levels. Ladle refining, vacuum degassing, and other secondary metallurgical processes play an important role in minimizing the content of harmful elements that contribute to hot shortness.

Solidification Behavior and Microsegregation

During solidification, impurities often segregate toward the final areas to solidify—usually the grain boundaries or interdendritic regions. This microsegregation concentrates low-melting-point compounds in areas that are most vulnerable to mechanical stress during thermal processing. The presence of these localized zones is a key mechanism behind the onset of hot shortness and emphasizes the importance of controlled cooling and uniform solidification during casting.

How to Detect Hot Shortness in Manufacturing

Visual and Surface-Level Inspection

The initial signs of hot shortness often appear during or after high-temperature processing, such as forging, rolling, or welding. Visual inspection can reveal surface cracks that follow grain boundaries, typically appearing as shallow, intergranular fissures. These cracks may not be evident in the as-cast condition but become visible when the material is deformed at elevated temperatures. While useful, visual inspection alone is insufficient for detecting internal or subsurface hot shortness defects.

Metallographic Examination

Microscopic analysis is a reliable method to identify hot shortness, especially in its early stages. Metallographic samples are prepared from affected areas and examined under optical or electron microscopes. Intergranular cracking, sulfide inclusions, and signs of localized melting can be observed directly. These indicators confirm the presence of hot shortness and help distinguish it from other brittleness phenomena. Grain boundary segregation of copper or sulfur compounds is often visible through etching and imaging techniques.

Chemical Composition Testing

Analyzing the chemical composition of the steel is essential for assessing the risk of hot shortness. Optical emission spectroscopy (OES) and inductively coupled plasma (ICP) analysis are commonly used to measure the levels of sulfur, copper, manganese, and other residual elements. Particular attention is given to the manganese-to-sulfur ratio, which should be sufficient to avoid the formation of iron sulfide. If copper content is above threshold values, especially in scrap-based steel, the likelihood of hot shortness increases.

Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

Ultrasonic testing (UT) and eddy current testing are valuable non-destructive methods for detecting subsurface cracks or inhomogeneities caused by hot shortness. Ultrasonic waves can reflect from internal fissures formed during forging or rolling, while eddy current testing can reveal surface-breaking defects related to grain boundary weakness. Though not specific to hot shortness, these methods are useful in identifying crack patterns consistent with thermally induced brittleness.

Hot Ductility Testing

Hot ductility tests provide a direct assessment of how steel behaves under elevated temperatures. In this test, a small sample is heated to specific processing temperatures and mechanically strained to observe its ability to deform without cracking. The resulting data offers insight into the temperature range in which the material loses ductility—a key indicator of hot shortness. This method is especially relevant in evaluating steel grades intended for forging or rolling.

Application of Process Monitoring

In modern manufacturing environments, thermal and mechanical parameters are closely monitored during processing. Deviations in furnace temperature, cooling rates, or deformation speeds can influence the occurrence of hot shortness. By tracking these parameters in real time, manufacturers can identify process conditions that may promote cracking. Data analysis tools integrated into production systems allow for early warnings and process adjustments to avoid quality losses.

How to Prevent Hot Shortness in Steel Production

Control of Chemical Composition

Preventing hot shortness begins with precise control over the steel’s chemical composition. Sulfur content must be kept below critical levels to minimize the formation of low-melting-point iron sulfide (FeS). Manganese is added intentionally during steelmaking to bind with sulfur and form manganese sulfide (MnS), which is less harmful. The optimal manganese-to-sulfur ratio is typically maintained above 8:1 to ensure effective neutralization. Monitoring this ratio in real time helps prevent the formation of FeS, which is a primary contributor to grain boundary weakening at high temperatures.

Selection of Low-Residual Raw Materials

The use of low-residual raw materials is a key strategy, especially in facilities that rely on scrap-based production. Copper and other residual elements are difficult to remove during secondary refining, and their accumulation increases the risk of hot shortness. Selecting scrap with known composition and minimal copper content, or blending it with virgin material to dilute impurities, is essential in maintaining quality. In electric arc furnace (EAF) operations, this step is particularly critical.

Need Help? We’re Here for You!

Application of Secondary Metallurgy

Secondary refining techniques such as ladle metallurgy, vacuum degassing, and argon oxygen decarburization (AOD) play a central role in reducing impurity levels. These processes allow for better control of sulfur, phosphorus, and other residual elements. Through the use of fluxes and gas stirring, impurities are removed from the melt or converted into harmless compounds. These steps enhance the cleanliness of the steel and reduce susceptibility to hot shortness during subsequent hot working.

Use of Alloying Elements to Modify Grain Boundaries

In some steel grades, alloying elements such as titanium, zirconium, or rare earth metals are introduced to refine grain structure or modify the behavior of sulfide inclusions. These elements form stable compounds that do not promote intergranular melting. Additionally, they can help improve grain boundary cohesion, making the steel more resistant to hot shortness. Their application is typically found in specialized steels for demanding environments.

Optimized Casting and Cooling Conditions

The control of solidification parameters during casting affects the distribution of impurities. Uniform cooling and minimized microsegregation during solidification help limit the concentration of low-melting-point phases at grain boundaries. Continuous casting processes with controlled secondary cooling zones and appropriate mold fluxes help achieve consistent metallurgical structure. Slower or uneven cooling can exacerbate microsegregation, increasing the risk of hot shortness during further processing.

Process Design and Operational Adjustments

Adjusting process parameters such as reheating temperature, strain rate, and deformation temperature during forging or rolling can help mitigate the effects of existing hot shortness tendencies. Operating outside the critical temperature range where ductility is reduced can prevent crack formation. In rolling mills, reducing rolling force or modifying pass schedules for susceptible steel grades helps avoid inducing mechanical stress when the material is most vulnerable.

The Impact of Hot Shortness on Product Quality

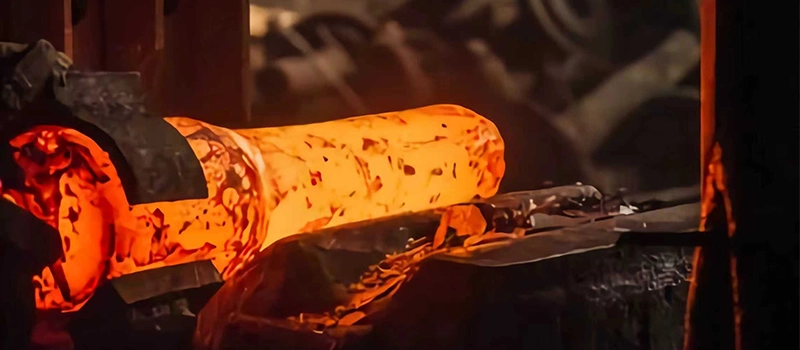

Formation of Cracks During Hot Working

Hot shortness primarily manifests during high-temperature forming operations such as forging, rolling, and extrusion. When steel with uncontrolled levels of sulfur or copper is subjected to mechanical stress within the hot shortness temperature range, cracks can initiate along weakened grain boundaries. These cracks may not be immediately visible but can propagate during further processing, leading to dimensional defects or complete part failure.

Reduced Mechanical Strength and Reliability

The presence of intergranular cracks significantly lowers the mechanical strength of steel components. These defects act as stress concentrators, reducing both tensile strength and fracture toughness. Components subjected to dynamic or cyclic loading, such as automotive shafts, pressure vessel components, or structural connectors, become more prone to fatigue failure. Even small internal cracks can compromise long-term reliability, particularly in safety-critical applications.

Implications for Welding and Joining

Hot shortness also affects weldability. In steels with high sulfur or copper content, cracking may occur in the heat-affected zone (HAZ) during welding. Elevated temperatures in the HAZ can promote local melting of grain boundary phases, leading to intergranular cracking upon solidification. This weakens the joint and may necessitate post-weld heat treatment or complete rework. Proper selection of filler materials and pre-weld inspection are required to mitigate these risks.

Rework, Scrap, and Production Downtime

Components affected by hot shortness often require reworking or complete rejection. This leads to increased scrap rates, higher production costs, and disruptions in manufacturing schedules. For high-volume production environments, even a small percentage of rejected parts can result in substantial economic loss. Additional time spent on inspections, metallurgical analysis, and corrective action also contributes to operational inefficiencies.

Impact on Quality Assurance and Certification

Products exhibiting hot shortness-related defects are unlikely to pass non-destructive testing or mechanical property validation required for certification. Regulatory standards—particularly for exports to regions like the European Union—demand that steel components meet specific mechanical and structural performance criteria. Failure to comply can result in shipment delays, certification issues, or contractual penalties.

Risks in Field Applications

The presence of hot shortness-related damage in finished components poses a long-term reliability risk. In service environments involving thermal cycling, vibration, or mechanical loading, previously undetected microcracks may propagate and lead to in-service failures. In sectors such as construction, energy, and transportation, such failures can result in equipment damage, safety hazards, or operational shutdowns.

Conclusion

Hot shortness is a critical metallurgical issue that can compromise the performance and reliability of steel alloys during high-temperature processing. Its occurrence is strongly influenced by impurity content, particularly sulfur and copper, and becomes evident under thermal and mechanical stress. Effective prevention relies on precise control of chemical composition, refining processes, and forming conditions. For manufacturers aiming to meet international quality standards, especially those exporting to regulated markets, early detection and mitigation of hot shortness is essential to ensure product integrity and maintain consistent production quality.