Are your copper castings warping during cooling? Are you seeing defects, inconsistent fills, or failed joints in forged parts? Do you wonder whether you’re applying the right heat but still getting unpredictable results?

Even a small deviation from the correct melting point of copper can lead to structural weakness, porosity, wasted material, or total production failure. Without clear control over this temperature, even the best equipment and processes can’t guarantee quality. In large-scale production, these issues directly result in higher costs and lower output consistency.

That’s why understanding the melting point of copper—1,085°C or 1,984°F—is essential in forging and casting. In this article, I’ll walk you through everything you need to know: how copper melts, what affects its melting behavior, how it compares to other metals like aluminum and zinc, and how to control the melting process efficiently. If you work with copper, this knowledge isn’t optional—it’s the foundation of successful production.

What Is the Melting Point of Copper?

The exact melting point of copper

The melting point of copper is precisely 1,085 degrees Celsius, which is equivalent to 1,984 degrees Fahrenheit or 1,358 Kelvin. This is the temperature at which pure copper transitions from solid to liquid under standard atmospheric pressure. Unlike alloys or impure metals, pure copper has a sharp melting point, not a range, because it is a single-element metal with a uniform atomic structure.

How copper behaves when it reaches melting point

At its melting point, copper undergoes a phase change: its tightly packed crystal lattice breaks down into a liquid form. This change is instant and complete, making copper highly predictable during thermal processes. Once it reaches 1,085°C, any additional heat causes rapid liquefaction, which is essential for clean mold filling during casting and precise heat control in industrial applications.

Temperature reference table

To aid professionals in various industries, here’s a quick reference for copper’s melting point in all three major units:

| Temperature Scale | Melting Point of Copper |

|---|---|

| Celsius (°C) | 1,085°C |

| Fahrenheit (°F) | 1,984°F |

| Kelvin (K) | 1,358 K |

Boiling vs. Melting Point of Copper: What’s the Difference?

Understanding the difference between melting and boiling

While the melting point of copper refers to the temperature at which it changes from a solid to a liquid, the boiling point refers to the temperature at which liquid copper becomes a gas. These are two very different physical phenomena that occur at vastly different temperatures and play unique roles in metalworking.

- Melting Point of Copper: 1,085°C (1,984°F)

- Boiling Point of Copper: 2,562°C (4,644°F)

In metalworking processes like casting or forging, we work around the melting point, not the boiling point. Reaching the boiling point of copper in standard manufacturing is extremely rare, and doing so would be not only energy-intensive but also risky, as copper vapors can oxidize rapidly and release toxic fumes.

Why the boiling point matters less — but still matters

Although boiling copper is not part of most practical processes, knowing its boiling point is useful in specific high-temperature applications, such as:

- Vacuum metallization

- Advanced welding techniques (e.g., plasma arc)

- Aerospace-grade component fabrication

In these scenarios, extreme temperatures may approach or even exceed copper’s boiling point, requiring specialized equipment and inert atmospheres to prevent oxidation or material loss. However, for standard forging, casting, or machining, your concern should remain well below the boiling point — and focused on controlling temperatures around the melting point.

Factors That Influence the Melting Point of Copper

The impact of impurities and alloying elements

Pure copper has a fixed melting point of 1,085°C (1,984°F), but in real-world manufacturing, it’s rare to work with 100% pure copper. The presence of impurities, traces of other elements, or intentional alloying can significantly affect how copper behaves under heat. For example, adding small amounts of tin, zinc, or nickel will lower the melting point and change the solidification behavior. These changes aren’t accidental—they’re often used to improve castability, reduce oxidation, or tailor the mechanical properties of the final product.

Even trace contaminants like iron, lead, or oxygen can influence copper’s melting and flow behavior. In precision casting or forging operations, these impurities can cause non-uniform heating, porosity, and brittleness. That’s why metallurgical analysis of input materials is a necessary step in quality control.

How copper compounds affect melting point

When copper exists as a compound, its melting point is no longer the same as metallic copper. These compounds include:

- Copper(II) chloride (CuCl₂): Melting point ~498°C

- Copper nitrate (Cu(NO₃)₂): Melting point ~114°C (decomposes)

- Copper(II) sulfate (CuSO₄): Melting point ~560°C

These materials are typically used in chemical processes or laboratory work, not in casting or forging. However, it’s important not to confuse these substances with metallic copper. In some cases, these compounds may form surface layers on copper during oxidation or corrosion, altering how the metal behaves when reheated.

If these byproducts are not removed before remelting, they can interfere with heat transfer, lower structural integrity, or contaminate molds. That’s why deoxidation and flux treatment are essential steps in re-melting recycled copper scrap.

Does the form of copper affect its melting point?

A common question we hear is: “What is the melting point of copper pipe or copper wire—does the shape change the melting temperature?” The answer is no. Shape does not affect melting point. Whether it’s a sheet, rod, pipe, or wire, if the material is pure copper, its melting point remains 1,085°C.

However, the surface area and thickness of the copper object can influence how fast it heats, which may give the illusion of different melting behavior. For example:

- Thin copper wire may melt faster because it reaches 1,085°C more quickly

- Thick copper tubing takes longer to heat uniformly

This doesn’t change the actual melting point—only the thermal response. The only case where form can indirectly affect melting behavior is when it comes with manufacturing differences, such as internal oxidation, coatings, or residual stress, which may influence how the copper behaves once heated.

Melting Point of Copper Alloys

Copper vs. Copper-Nickel Alloys

Copper-nickel alloys, often known as cupronickel, are widely used in marine, electrical, and heat exchanger applications due to their excellent corrosion resistance and strength. However, when nickel is added to copper, it raises the melting point slightly depending on the composition. For example:

- 70/30 Cu-Ni (70% copper, 30% nickel): Melting range of 1,180–1,246°C

- 90/10 Cu-Ni (90% copper, 10% nickel): Melting range of 1,100–1,145°C

The presence of nickel increases the bonding energy between atoms, requiring more heat to transition the alloy into a liquid. This is important to consider when switching from pure copper to copper-nickel in casting or welding — your furnace settings will need to be adjusted accordingly.

Copper Solder and Its Lower Melting Point

One of the most common applications of modified copper is in soldering. Copper-based solders are engineered to melt at lower temperatures for joining pipes, wires, or electronic components without damaging them.

- Phosphorus-Copper Solder: ~710–890°C

- Silver-Copper Solder: ~620–800°C

In these cases, other elements like phosphorus, tin, or silver are added specifically to reduce the melting point and improve flow characteristics. The goal is to create a strong bond without reaching copper’s full melting point, which could deform the base metal.

Need Help? We’re Here for You!

So, when people ask, “What is the melting point of copper solder?” — the answer depends on the alloy formula, but it’s always lower than pure copper for easier handling.

Melting Point of Brass and Bronze

Both brass and bronze are alloys of copper, but they differ in both composition and melting behavior.

- Brass = Copper + Zinc

- Bronze = Copper + Tin (often with other elements like aluminum or phosphorus)

Here’s a look at their typical melting ranges:

| Alloy Type | Composition | Melting Point Range |

|---|---|---|

| Brass | Cu + Zn (varies) | 900–940°C |

| Bronze | Cu + Sn (varies) | 950–1,050°C |

| Pure Copper | 100% Cu | 1,085°C |

Because zinc and tin both have lower melting points than copper, these alloys typically melt below pure copper. This makes them more castable, but also more prone to oxidation and off-gassing during melting, especially in open air.

Melting Point of Copper Compared to Other Metals

Understanding how copper’s melting point compares with other industrial metals is essential when selecting materials for casting, forging, machining, or heat treatment. Different metals melt at different temperatures, which directly influences their formability, cooling rate, energy cost, and suitability for specific applications.

Copper vs. Aluminum

- Copper Melting Point: 1,085°C

- Aluminum Melting Point: 660°C

Aluminum melts at a much lower temperature than copper, making it easier and cheaper to process, especially in large volumes. However, aluminum is also softer and less conductive than copper. In applications requiring thermal or electrical efficiency (like power systems or electronics), copper is still the preferred choice despite its higher melting point.

Copper vs. Zinc

- Copper Melting Point: 1,085°C

- Zinc Melting Point: 419°C

Zinc has an extremely low melting point, which is why it’s often used in die casting and galvanization. In fact, many copper alloys (like brass) include zinc to lower the overall melting temperature and make the material easier to mold. However, zinc burns off quickly at high temperatures and can release harmful fumes, requiring careful process control.

This is why melting point of zinc and copper comparisons are crucial when dealing with brass production or recycling.

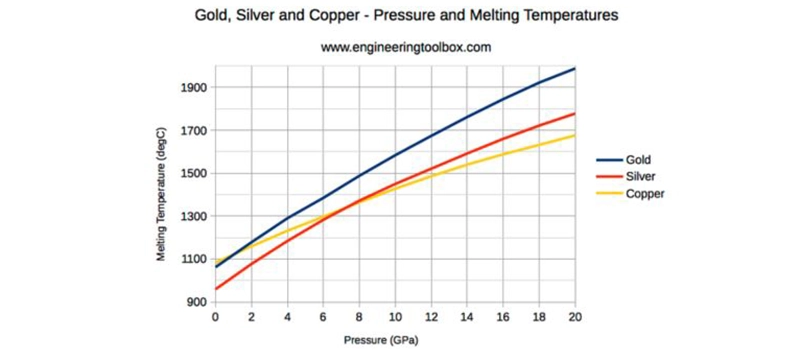

Copper vs. Silver and Gold

- Copper: 1,085°C

- Silver: 961°C

- Gold: 1,064°C

Surprisingly, both silver and gold melt at lower temperatures than copper, despite being considered precious and “softer” metals. This lower melting point makes them easier to work with in fine casting, jewelry, and electrical contacts. However, copper’s higher melting point makes it more stable in high-temperature industrial settings, such as welding electrodes, heat exchangers, and foundry tooling.

Copper vs. Iron and Steel

- Copper: 1,085°C

- Iron: 1,538°C

- Carbon Steel: ~1,420–1,500°C

- Stainless Steel: ~1,400–1,530°C

Iron and steel melt at much higher temperatures than copper, which has several implications:

- Requires more energy to melt

- Needs high-grade furnace linings

- Offers higher temperature resistance in final products

This is why copper and steel are often used together in assemblies but processed separately, with different heating, handling, and cooling requirements.

Quick Comparison Table

| Metal | Melting Point (°C) | Melting Point (°F) |

|---|---|---|

| Zinc | 419°C | 786°F |

| Aluminum | 660°C | 1,220°F |

| Silver | 961°C | 1,762°F |

| Gold | 1,064°C | 1,947°F |

| Copper | 1,085°C | 1,984°F |

| Bronze (alloy) | 950–1,050°C | 1,742–1,922°F |

| Brass (alloy) | 900–940°C | 1,652–1,724°F |

| Iron | 1,538°C | 2,800°F |

| Carbon Steel | ~1,420–1,500°C | ~2,588–2,732°F |

| Stainless Steel | ~1,400–1,530°C | ~2,552–2,786°F |

Why these comparisons matter

Choosing the right metal for your application means balancing performance, cost, processing temperature, and machinability. For example:

- If energy cost is a concern → Aluminum or Zinc

- If high heat resistance is needed → Iron or Steel

- If conductivity and formability are essential → Copper or Silver

When working in mixed-material systems, like copper pipes with brass fittings or copper windings in steel housings, knowing the relative melting points ensures your process temperatures don’t compromise any part of the assembly.

Why the Melting Point of Copper Is Critical in Industry

The melting point of copper—1,085°C (1,984°F)—is a benchmark that governs nearly every industrial process involving copper. From the casting floor to machining centers and heat treatment lines, this number isn’t just data—it’s the foundation of temperature planning, energy control, and product integrity.

In copper casting, precise control around the melting point of copper metal ensures clean fills, smooth solidification, and minimal porosity. Undermelting results in incomplete molds or cold shuts; overheating causes oxidation, excessive slag, and thermal damage. That’s why understanding and respecting the melting point of copper in celsius is essential for achieving consistent product quality.

In forging, we avoid reaching the melting point directly, instead working copper in a heated but solid state (700–900°C). This approach softens the metal while preserving its grain structure. Without knowing the true melting point of copper, it’s impossible to calculate safe forging temperatures or optimize deformation efficiency.

In machining, localized heat can build up due to friction. While operations typically stay below the melting point of copper, lack of temperature awareness can lead to tool damage, poor surface finishes, and tolerance drift—especially in high-speed or dry cutting environments.

Furthermore, the melting point of copper plays a central role in thermal cycle design. In heat treatment, stress relief, or annealing operations, engineers design precise heating curves that stay well below the melting point to alter mechanical properties without compromising structural integrity. Even small miscalculations near the melting point of copper metal can result in warping, softening, or grain boundary failure.

In quality assurance, thermal control protocols are written with the melting point of copper as the upper threshold. Temperature sensors, infrared cameras, and induction control systems are all calibrated to avoid crossing this limit, ensuring every product meets dimensional, conductive, and mechanical standards.

Techniques for Efficiently Melting Copper

Efficiently melting copper is not just about reaching 1,085°C, the melting point of copper metal. It’s about controlling the process so the copper melts evenly, cleanly, and with minimal oxidation or energy waste. In industrial applications, we rely on a range of melting techniques tailored to volume, precision, and product type. Below, I’ll break down the most common and effective methods used today to reach and manage the melt point of copper safely and efficiently.

Induction Melting: Clean and Precise for Industrial Foundries

Induction melting is one of the most efficient and controlled ways to reach the melting point of copper. This method uses alternating electromagnetic fields to generate heat inside the copper itself, allowing for:

- Rapid, even heating

- Low contamination risk (no combustion gases)

- Precise temperature control right around 1,085°C

- Ideal for high-purity castings or critical components

Induction furnaces are common in copper foundries that produce rotor parts, electrical terminals, or precision fittings, where maintaining exact control at the melting point of copper metal is crucial to avoid overburning or slag inclusion.

Crucible Melting: Widely Used in Small to Medium Batch Production

Crucible melting is a traditional method that remains widely used in small foundries, workshops, or batch production environments. The crucible—often made of graphite, silicon carbide, or ceramic—holds the copper as it’s heated indirectly in a fuel-fired or electric furnace.

- Requires constant monitoring to avoid exceeding the melting point of copper

- Often reaches 1,100–1,150°C to ensure full liquefaction and pourability

- Needs fluxes or cover agents to protect the surface from oxidation

While not as precise as induction, crucible melting is flexible and cost-effective, especially for jobs like copper art casting, bushings, and non-critical fittings.

Resistance Furnaces: Best for Lab and Alloy Testing

For research, lab-scale melting, or testing copper alloy behavior, resistance furnaces offer a clean and reliable method to control the melt point of copper. These electric furnaces use heated coils and insulation to slowly and evenly bring copper to its melting point.

- Excellent for material testing and melting point verification

- Not energy-efficient for high-volume production

- Useful for alloy development and thermal experiments in a controlled setting

This method is ideal when studying melting point of copper solder, copper-nickel alloys, or comparing copper with aluminum or zinc.

Key Tips for Controlling the Melt Point of Copper

Regardless of the melting method, there are universal best practices that help control the melting point of copper and ensure smooth operation:

- Use temperature sensors (pyrometers or thermocouples) calibrated for ≥1,100°C

- Always melt in a reducing or neutral atmosphere to avoid oxidation

- Preheat crucibles to reduce thermal shock and energy loss

- Avoid overheating above 1,150°C to preserve grain structure and reduce dross

- Use high-purity charge materials to maintain a sharp melt point and reduce slag

Conclusion

Mastering the melting point of copper is essential for precision, quality, and efficiency in modern metalworking. From casting to forging, understanding how copper behaves at 1,085°C helps manufacturers optimize processes, reduce waste, and deliver high-performance components across every industry.