Why do hardened mechanical components made from 420 stainless steel show cracking after heat treatment?

Why do shafts, pins, or valve parts distort even when machining dimensions were correct?

Why does hardness look acceptable, yet parts fail early in service?

These problems usually appear when 420 stainless steel is selected without fully considering its application limits and processing behavior.

The ASM Handbook on Heat Treating notes that martensitic stainless steels require precise control of austenitizing temperature, quenching rate, and tempering strategy to balance hardness and toughness.

420 stainless steel is commonly used in hardened mechanical components, but its performance is highly dependent on how heat treatment and machining are coordinated with the intended service conditions.

Understanding how 420 stainless steel behaves in hardened mechanical components is essential to achieve reliable hardness, dimensional stability, and acceptable service life in real industrial applications.

What 420 Stainless Steel Is in Mechanical Applications

Classification of 420 Stainless Steel

420 stainless steel is a martensitic stainless steel grade designed to be hardened through heat treatment. In mechanical applications, it is not selected for general corrosion resistance or ease of fabrication, but for its ability to achieve relatively high hardness while maintaining basic stainless properties. Its behavior is defined by the balance between carbon content, chromium level, and heat treatment control.

From an application perspective, 420 stainless steel sits between low-carbon martensitic grades and higher-carbon wear-focused grades. It offers more hardness than structural martensitic steels, but with less brittleness than higher-carbon alternatives when processed correctly.

Why 420 Stainless Steel Is Chosen for Hardened Components

420 stainless steel is commonly used in hardened mechanical components because it can reach useful hardness levels while remaining machinable before heat treatment. This makes it suitable for parts that require precise geometry first and surface durability later.

In real applications, the material is chosen when wear resistance and dimensional stability after hardening are more important than impact toughness or high corrosion resistance. Typical selection drivers include controlled hardness, moderate cost, and predictable response to standard heat treatment cycles.

Typical Supply Condition and Processing Route

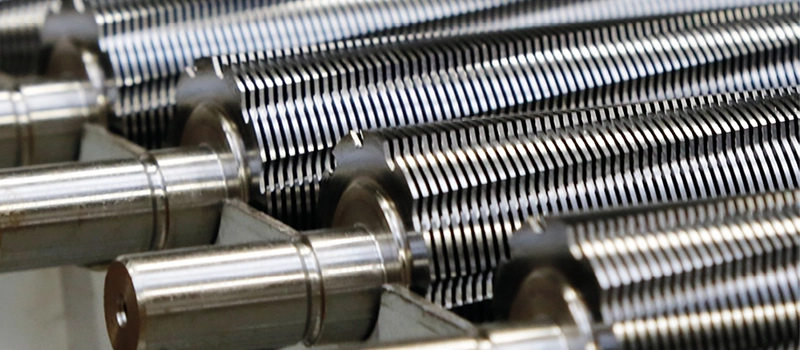

420 stainless steel is typically supplied in an annealed or softened condition to allow machining. Most mechanical components are fully machined to near-final dimensions before hardening. Heat treatment is then applied to achieve the required hardness and wear performance.

After hardening, only minimal finishing is normally acceptable. Grinding or corrective machining introduces risk due to increased hardness and reduced toughness. For this reason, the standard processing route for 420 stainless steel in mechanical applications relies on accurate pre-heat-treatment machining and disciplined thermal control.

Chemical Composition and Its Application Implications

Carbon Content and Achievable Hardness

The carbon content of 420 stainless steel is the primary factor that enables hardening through heat treatment. In mechanical components, this carbon level allows the material to reach hardness values suitable for wear resistance without pushing the structure into extreme brittleness when tempering is properly controlled.

From an application standpoint, higher hardness is useful only when it remains stable and uniform across the part. Variations in carbon distribution or section thickness can lead to uneven hardness after quenching, which directly affects wear behavior and dimensional stability. For this reason, component geometry and heat treatment parameters must be matched to the material’s carbon-driven response.

Chromium Content and Corrosion Limits

Chromium in 420 stainless steel provides basic corrosion resistance and supports martensitic transformation. However, its chromium level is optimized for hardenability rather than aggressive corrosion environments. In practical applications, this means the material performs adequately in dry or mildly corrosive conditions but degrades quickly in chloride-rich or continuously wet environments.

Heat treatment and surface condition strongly influence corrosion behavior. Improper thermal control or surface damage during machining and grinding reduces the effectiveness of the passive layer. In mechanical components where corrosion exposure exists, chromium content alone should not be relied upon to ensure durability.

How Composition Affects Component Reliability

The combined effect of carbon and chromium defines how 420 stainless steel behaves in service. High hardness improves wear resistance, but reduced toughness increases sensitivity to stress concentration and impact loading. This balance is acceptable for many hardened mechanical components, provided the application loads are well understood.

Reliability issues often arise when the material is used outside its intended envelope, such as in high-impact assemblies or environments with fluctuating thermal or corrosive conditions. Understanding how composition limits performance helps ensure that 420 stainless steel is applied where its strengths are effective and its weaknesses are manageable.

Heat Treatment Behavior of 420 Stainless Steel in Practice

Annealed Condition and Pre-Hardening Machining

420 stainless steel is normally supplied in an annealed condition to allow machining before hardening. In this state, cutting stability is acceptable and dimensional control can be maintained with standard tooling strategies. For hardened mechanical components, this stage is critical because most functional geometry must be established before heat treatment.

Residual stress introduced during machining often remains hidden until quenching. Aggressive cutting parameters, poor chip control, or excessive heat buildup increase the likelihood of distortion later. For this reason, machining strategy should prioritize stability over speed, with the expectation that post-hardening correction options are limited.

Austenitizing Control for Mechanical Parts

Austenitizing temperature directly influences final hardness and microstructural uniformity. If the temperature is too low, transformation is incomplete and hardness targets are not achieved. If it is too high, grain growth increases brittleness and raises distortion risk.

For mechanical components with varying section thickness, uniform heat input is as important as the nominal temperature value. Uneven heating leads to hardness variation across the part, which affects wear behavior and assembly fit. Consistent soak time and controlled furnace loading are therefore essential.

Quenching Methods and Distortion Risk

Quenching transforms the austenitized structure into hard martensite, but it is also the stage where most dimensional instability occurs. Faster quenching increases hardness potential but significantly raises internal stress. Slower quenching reduces stress but may compromise hardness consistency.

Distortion risk increases with asymmetric geometry, sharp transitions, and uneven section thickness. Mechanical components such as shafts or valve parts are especially sensitive to quench-induced warping. Selecting an appropriate quenching medium and controlling part orientation are key to minimizing deformation.

Tempering Strategy for Hardness–Toughness Balance

Tempering reduces brittleness and stabilizes hardness after quenching. Insufficient tempering leaves residual stress in the structure, while excessive tempering reduces hardness beyond functional requirements. For hardened mechanical components, the acceptable tempering window is narrow.

Consistent tempering cycles are necessary to achieve repeatable results across batches. Variability at this stage often explains why parts with identical machining and quenching histories perform differently in service.

Common Heat Treatment Failures in Mechanical Components

Typical failures include quench cracking, excessive distortion, and uneven hardness distribution. These issues are usually caused by poor temperature control, inappropriate quenching methods, or inadequate stress relief before hardening. In most cases, correcting these problems requires tighter process control rather than material substitution.

Machining Considerations for Hardened Mechanical Components

Machining Before Heat Treatment

For 420 stainless steel, machining before heat treatment is the preferred and most stable approach. In the annealed condition, the material allows predictable cutting behavior and acceptable tool life. This stage is where critical dimensions, alignment features, and surface geometry should be established as completely as possible.

From an application standpoint, machining strategy should aim to minimize residual stress. Heavy cuts, aggressive feeds, and localized overheating increase the likelihood of distortion during hardening. Stable cutting parameters and consistent material removal are more important than cycle-time optimization for parts intended to be hardened.

Dimensional Stability After Hardening

Once heat treatment is completed, dimensional stability becomes difficult to control. Even with proper process discipline, some level of distortion is unavoidable due to phase transformation and internal stress redistribution. For hardened mechanical components, this means tolerances must account for expected movement rather than assuming perfect shape retention.

Components with uniform cross-sections tend to behave more predictably. Features such as grooves, shoulders, and abrupt diameter changes increase distortion risk. Designing geometry with heat treatment behavior in mind is essential to maintaining assembly accuracy.

Risks of Post-Hardening Machining

Machining after hardening is generally limited to light grinding or finishing operations. At elevated hardness levels, 420 stainless steel exhibits reduced toughness and increased tool wear. Aggressive post-hardening machining introduces surface damage, microcracks, and localized heating that can compromise service life.

In mechanical applications, post-hardening correction should be treated as a last resort rather than a planned process step. Reliable results depend on achieving dimensional accuracy before heat treatment and minimizing material removal afterward.

Forming, Welding, and Assembly Limitations

Cold Forming Restrictions

420 stainless steel is not well suited for cold forming, especially when the component is intended to be hardened. Even in the annealed condition, ductility is limited compared with austenitic grades. Bending, stamping, or other forming operations introduce strain that increases the risk of cracking during subsequent heat treatment.

In mechanical applications, forming should be minimized or avoided entirely. Geometry is more reliably achieved through machining, where deformation can be controlled and residual stress managed before hardening.

Welding Crack Sensitivity in Mechanical Parts

Welding presents significant risk when using 420 stainless steel. During cooling, the heat-affected zone transforms into hard martensite, creating a brittle region prone to cracking. Preheating and post-weld heat treatment can reduce risk, but they do not eliminate it, especially in precision mechanical components.

From an application standpoint, welded joints introduce variability that is difficult to control after hardening. For this reason, designs that require welding are generally poor candidates for 420 stainless steel when dimensional stability and service reliability are critical.

Assembly Risks Caused by Residual Stress

Residual stress from machining and heat treatment directly affects assembly behavior. Hardened mechanical components may appear dimensionally correct individually but shift or bind when assembled due to stress release under load or constraint.

This effect is most evident in press fits, keyed assemblies, and multi-part systems where alignment is critical. Managing residual stress through conservative machining, controlled heat treatment, and appropriate tolerancing is essential to avoid assembly-related failures.

Surface Finish and Wear Performance

Surface Condition After Heat Treatment

After heat treatment, surface condition becomes a critical factor for component performance. Scale formation, decarburization, or uneven oxidation during hardening can alter surface hardness and introduce weak zones. For hardened mechanical components, these surface changes directly affect wear behavior and dimensional consistency.

Controlled atmosphere heat treatment or post-heat-treatment cleaning is often required to maintain a stable surface. Ignoring surface condition at this stage can negate the benefits of properly controlled hardness.

Grinding Heat and Microcrack Risk

Grinding is commonly used for final sizing, but it introduces localized heat that is difficult to control. In hardened 420 stainless steel, excessive grinding heat causes surface tempering or microcracking. These defects may not be visible during inspection but significantly reduce wear life and fatigue resistance.

From an application perspective, grinding parameters must be conservative. Sharp wheels, adequate cooling, and controlled material removal rates are essential to avoid thermal damage in hardened components.

Need Help? We’re Here for You!

Relationship Between Surface Finish and Wear Life

Wear resistance is not determined by hardness alone. Surface roughness, residual stress, and microstructural integrity all influence how a component performs in service. A rough or thermally damaged surface accelerates wear even when bulk hardness meets specification.

For mechanical components subjected to sliding or repeated contact, surface finish must be matched to the application. Proper control at this stage improves service life more effectively than increasing hardness beyond practical limits.

Conclusion

420 stainless steel is well suited for hardened mechanical components when its application limits are clearly understood. Reliable performance depends on controlled machining before heat treatment, disciplined thermal processing, and avoiding forming or welding operations. When these conditions are respected, the material delivers stable hardness and wear resistance; when they are not, dimensional and service failures become likely.